The Smith Center for the Performing Arts makes city cultural player

Las Vegas may not have a stadium -- or the major league team to go with it. (Yet.)

But when it comes to cultural venues, The Smith Center for the Performing Arts definitely puts Las Vegas in the major leagues.

And that's entirely by design.

Not only did Smith Center officials visit renowned cultural landmarks -- from New York's Carnegie Hall and Lincoln Center to Paris' Theatre des Champs Elysees and Milan's La Scala -- they even used templates of existing complexes to plan Las Vegas' downtown cultural center.

In the planning stages, "we would do overlays of exact models," seeking "a way to improve on what had been done before," explains Myron Martin, The Smith Center's president and chief executive officer.

The intent? To "create a new paradigm" that would instantly mark The Smith Center as "a world-class performing arts center," he says -- especially for more recent Southern Nevada transplants who "are accustomed to having world-class facilities."

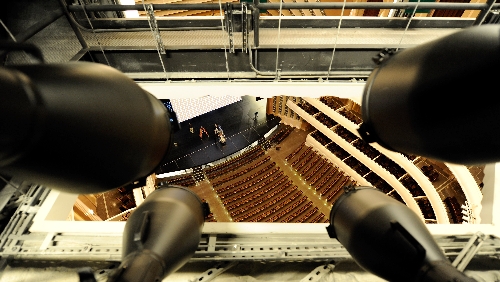

Reynolds Hall, The Smith Center's 2,050-seat auditorium, will host not only Nevada Ballet Theatre and Las Vegas Philharmonic programs but also touring Broadway shows and a variety of concerts and comedy performances.

In the adjacent Boman Pavilion, the 250-seat Cabaret Jazz club provides an intimate, two-tier setting for both jazz and cabaret performances, complete with a view overlooking Symphony Park. Rather than traditional theater seating, the club features tables and chairs on both the first and mezzanine levels, adding to the atmosphere, which Martin describes as if "a performing arts center and a jazz club collided."

Cabaret Jazz addresses "some things that weren't happening" in Las Vegas, he explains. "We didn't really have jazz and we didn't have cabaret -- but we knew there was demand for both."

Also in the Boman Pavilion, the Troesh Studio Theater serves as the center's version of a "black box" theater, with seating for 258.

The 3,000-square-foot space is designed for maximum flexibility, with multiple seating and stage configurations possible. Unlike most black box theaters, the Troesh theater has large windows, which are curtained to block light and distractions during performances. But the theater, complete with a designed-for-dancing sprung floor, also can serve as a rehearsal hall, a venue for corporate and community meetings -- and even private social gatherings, with room to host 240 sit-down diners.

Reynolds Hall and Cabaret Jazz are booked through July and June, respectively; the Troesh theater has productions scheduled in April and May.

Nothing's booked yet for a fourth planned performance space, outdoors in the adjacent Symphony Park, with lawn seating for 2,000 to 2,500, Martin says.

"We're giving a lot of thought" to possibilities for future outdoor concerts, he adds. "Stay tuned."

For now, however, the focus remains on The Smith Center's three indoor venues.

With its horseshoe-shaped, multitiered auditorium, Reynolds Hall's opera-house design represents a departure from the fan-shaped configuration most Las Vegas showrooms use, Martin acknowledges.

"At the end of the day, it was an important decision to make it something different than what people are accustomed to," he explains.

The auditorium Reynolds Hall most closely resembles is Bass Performance Hall in Fort Worth, Texas -- a "bigger, better Bass Hall," according to Matt Edwards of The Project Group, The Smith Center's lead project manager. (Edwards ought to know; he also worked on Bass Hall, which opened in 1998.)

Not only is The Smith Center's site bigger, "the lobbies are more spacious," Edwards says. So are the back-of-the-house dressing rooms and storage areas.

In addition, The Smith Center is "the first performing arts center of this size and scope to be LEED-certified," Edwards notes.

LEED stands for "Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design" -- and every project in downtown's 61-acre Symphony Park development is "required to be LEED-certified," according to Edwards. (The Smith Center has attained Silver LEED certification, the program's third-highest designation.)

As the old Union Pacific rail yard, the Symphony Park site was "contaminated with oil and gasoline, which (had) to be remediated," Edwards said .

Construction materials were recycled rather than trashed, diverting 75 percent of construction waste from landfills. About 10 percent of those materials were from regional suppliers. (The center's art deco-style lighting fixtures -- including the Grand Lobby's dramatic 19-foot chandeliers -- were fabricated in North Las Vegas.)

LEED requirements also called for low- and no-vapor paints, sealants and carpeting and underground duct work.

Reynolds Hall's air-conditioning ducts, for example, "are big enough to drive a Buick through," Martin says. "They're moving lots of air, very slowly," from the floor to the auditorium, eliminating noise in the process.

The Smith Center's eco-friendly elements extend to water-efficient landscaping -- and low-flow bathroom fixtures.

Speaking of bathrooms, The Smith Center has 101 of them -- two-thirds of them designated for women. (By contrast, UNLV's 1,870-seat Artemus Ham Hall has 14 or 15 women's restrooms, Martin says.)

Reynolds Hall boasts a number of distinctive elements, from three ground-floor star dressing rooms (with windows!) to air- and temperature-controlled storage areas for concert grand pianos when they're not in use onstage.

With a hundred-foot drop between the stage floor to the top of the proscenium, a fly loft to rig large-scale scenery and an orchestra pit capable of seating 65 musicians, Reynolds Hall can handle the big touring shows, Edwards says.

And Las Vegas audiences can watch those Broadway shows in greater comfort, Martin points out -- in seats that are 22 inches wide, compared with the standard Broadway width of 18 to 19 inches.

About 3,600 workers built The Smith Center during the 32-month construction period, Edwards says, with 500 to 600 workers on the project at peak times.

It took some time for them to adjust to the center's demanding construction standards, he acknowledges.

"They'd been working on casinos their whole life," Edwards explains. "They know the casino's getting torn down in 15 years -- and they know they can cut corners."

But Smith Center officials "were telling every employee that this thing has to be built to last, so no one is cutting any corners," he adds. "Early on, it was a bit of a challenge," particularly when supervisors would point out problems on site visits -- and require construction personnel to redo their work.

But "once you set the expectation, people don't want to do it 12 times," Edwards observes, especially because "every little detail gets looked at a thousand times over."

Such attention to detail has helped to build the kind of world-class cachet The Smith Center seeks to project.

"It'll be a magnet," predicts Steve Loftin , president of the Cincinnati Arts Association, which operates a downtown performing arts center that's "very comparable" with The Smith Center's three performance spaces.

"There's no question that a world-class facility will create opportunity for entertainment options," Loftin says, causing "the industry to react to a new hall, a new place to go and a new audience being developed."

That's already happening, Martin says.

"It's unbelievable; all the agents that have avoided Las Vegas in the past are now calling and saying, 'I know you have the place,' " he says, a touch of wonder in his voice. "For the first time, we are the talk of the arts and cultural world."

Contact reporter Carol Cling at ccling@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0272.