Beyoncé rides into Vegas in support of landmark new album

Beyoncé flexes a biceps, her smile briefly transformed into a grimace — she’s showing her teeth, literally and figuratively.

“A tough girl, I had to be,” she sings amid strains of fleetly picked banjo and simmering horns, her words to be tested soon enough.

It’s the 50th annual Country Music Awards in November 2016, and Beyoncé is onstage with The Chicks and a large backing band highlighted by a feisty washboard player and a leg-kicking alto saxophonist in bedazzled cowboy boots.

They’re knocking the stuffing out of “Daddy Lessons,” Beyoncé’s first foray at a country-leaning single from her alternately bruised and bruising avant R&B/art pop masterwork “Lemonade.”

True to the song’s title, lessons would be learned, all right — and taught as well, in the immediate aftermath of what would prove to be an equally polarizing and watershed performance, becoming the highest-rated 15 minutes in CMA history.

The backlash was swift: An online uproar ensued among some fans who objected to a pop superstar like Beyoncé taking the stage at the CMAs — even though this kind of crossover performance has long been fairly routine, with Justin Timberlake and Ariana Grande having played the CMAs in the two years prior, to cite just a couple of examples.

Among the cheesed off: Country singer Travis Tritt, who expressed his displeasure in a social media post.

“I don’t think there was anything ‘country’ about it. It was a pop song done by pop artists,” he wrote.

“As I see it, country music has appealed to millions for many years,” he added. “We can stand on our own and don’t need pop artists on our awards shows.”

‘I did not feel welcomed’

The pushback stung the Queen Bey.

After all, Beyoncé hails from Texas and grew up attending the Houston Livestock Show and Rodeo with her family in full cowboy gear.

She’s no stranger to a Stetson, no cultural carpetbagger when it comes to the community in question.

As she’d later explain on social media, the criticism felt personal, like something that went beyond the music.

And so she wrote a song about it — actually, it was closer to 100: That’s reportedly the number of tunes Beyoncé culled from to create her latest record.

“This album has been over five years in the making,” she wrote in an Instagram post in March 2024, shortly before its release. “It was born out of an experience that I had years ago where I did not feel welcomed … and it was very clear that I wasn’t.”

With 27 tracks and a 78-minute run time, it’s a lot to digest sonically, socially, thematically, politically, with “Cowboy Carter” tracing the history of African American contributions to the genre while simultaneously adding to it, with contributions from Black country musicians such as Tanner Adell, Brittney Spencer, Reyna Roberts, Shaboozey, Tiera Kennedy and Willie Jones.

Does genre matter?

It’s unquestionably a landmark release: At the Grammy Awards in February, Beyoncé became the first African American artist to win Best Country Album and the first Black woman to earn Album of the Year in over 25 years.

Her single “II Most Wanted” was also named Best Country Duo/Group Performance and was the first country song by a Black woman to top the Billboard Hot 100.

Despite the accolades, the questions linger: Is “Cowboy Carter” country? Is it not? Does it matter?

As Beyoncé returns to Allegiant Stadium for a pair of shows this weekend on her “Cowboy Carter World Tour,” the back-and-forth remains heated: Late last month, country singer Gavin Adcock publicly expressed his displeasure with “Cowboy Carter” being included on the country music charts.

“I really don’t believe her album should be labeled as country music,” he said in a social media video post. “It doesn’t sound country, it doesn’t feel country, and I just don’t think that people that have dedicated their whole lives to this genre and this lifestyle should have to compete or watch that album just stay at the top just because she’s Beyoncé.”

Big-tent country

“Genres are a funny little concept, aren’t they? Yes, they are,” Linda Martell notes in a spoken-word intro on “Cowboy Carter.” “In theory, they have a simple definition that’s easy to understand. But in practice, well, some may feel confined.”

She would know.

Not only was Martell the first Black woman to perform at the Grand Ole Opry, but she notched the first top-25 country hit by an African American woman with her cover of The Winstons’ “Color Him Father.”

Her words preface “Spaghettii,” in which Beyoncé raps at the most fevered clip of her career, her staccato bars flying by like the scenery outside a fast-moving car — “I ain’t no regular singer, now come get everythin’ you came for,” she growls at one point — with an assist from countrified singer-rapper Shaboozey.

“Spaghettii” is a snapshot of the creative fluidity at the heart of “Cowboy Carter,” juxtaposing a country pioneer (Martell), with a rising star (Shaboozey) while Beyoncé mines another genre entirely.

Her point: Country music is less a codified sound than a kind of big-tent Americana with innumerable entry points.

Blurred boundaries

And history underscores as much: From the get-go, country music has been posited on cross-pollination with other sounds and scenes. Genre pioneer Hank Williams mined the blues; ’70s outlaw country primer movers like Willie Nelson and Waylon Jennings took more than a few cues from Southern rock and folk; Dwight Yoakam brought rockabilly leanings into the fold in the ’80s.

A decade later, Garth Brooks shot to stardom, in part, by amplifying country with arena rock trappings, while Shania Twain lacquered everything in a hook-heavy pop sheen, paving the way for future superstar Taylor Swift, among plenty of others.

In more recent times, country has gone EDM beginning with Avicii’s 2014 hit “Hey Brother,” and hip-hop has become an increasingly prominent influence in Nashville circles. (See: Jason Aldean, Kane Brown, Florida Georgia Line, Brantley Gilbert, etc.)

When Willie Nelson is cutting tunes with Snoop Dogg, it’s kind of hard to double down on the ol’ country purism thing.

Speaking of Willie, he guests on “Cowboy Carter,” as does fellow country titan of song Dolly Parton, who introduces Beyoncé’s cover of her heart-in-a-vise classic “Jolene.”

As with pretty much everything on “Cowboy Carter,” though, Beyoncé turns traditionalism on its head during her take on the song, which she transforms from an entreaty to a warning.

“Jolene, I’m a woman, too / The games you play are nothing new / So you don’t want no heat with me,” she sings, before reminding her antagonist of her bona fides.

“I’m still a Creole banjee (expletive) from Louisianne.”

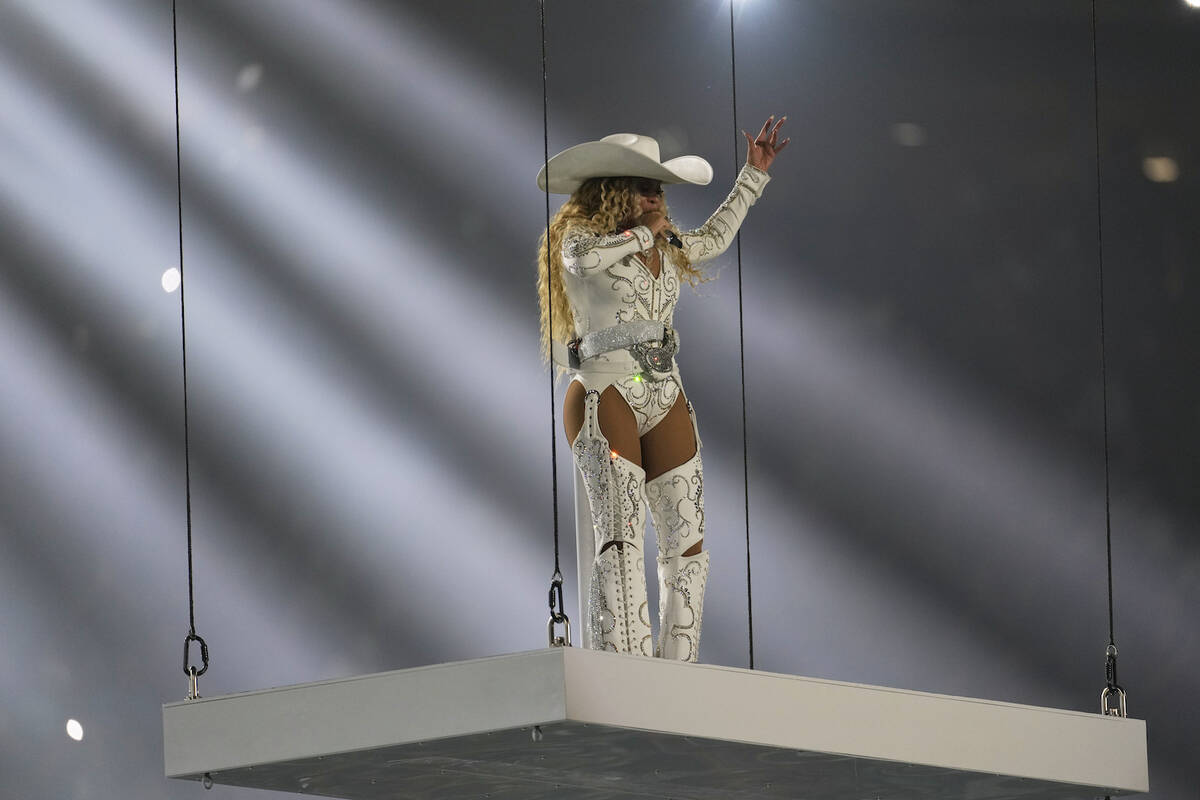

‘Cowboy’ on tour

“Jolene” comes three-quarters of the way through Beyoncé’s “Cowboy Carter” live production, prefacing “Daddy Lessons,” the song that started it all.

The show, running nearly three hours, is divided into eight acts spanning 41 songs, almost half of them from her latest album.

The outing has done blockbuster business around the globe, grossing more than $380 million and drawing over 1.5 million fans, though tickets remain for the two tour-closing dates in Vegas, as of press time.

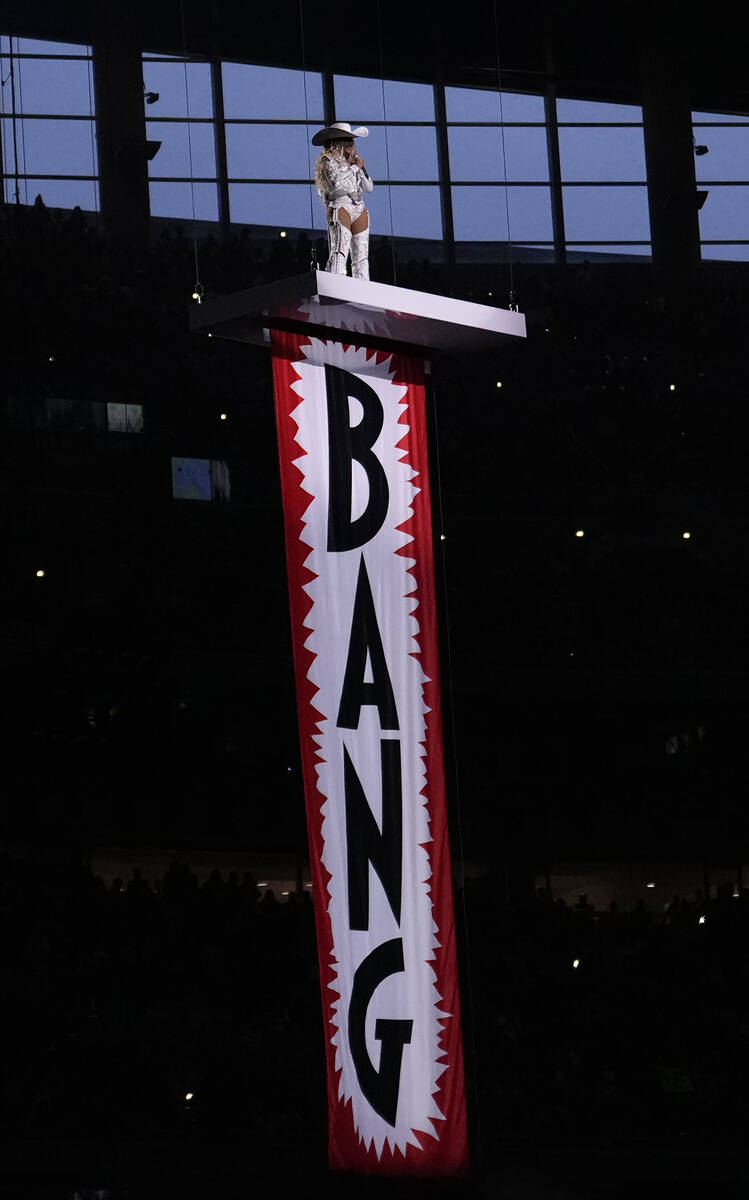

It’s designed to be a visually ostentatious yet politically charged performance, a blend of style and substance, with outsize stage props — at various points in the show, Beyoncé reportedly rides through the venue on a golden mechanical bull and a giant horseshoe — contrasted with images that speak to the themes of both racial and class inequality addressed on “Cowboy Carter” (a tattered American flag; a blindfolded Statue of Liberty).

During the first portion of the show, Beyoncé’s version of The Beatles’ “Blackbird,” a song inspired by the Civil Rights Movement, segues into “The Star-Spangled Banner,” the segment ending with “Ya Ya,” a full-on funk rebel yell.

‘If that ain’t country …’

“My family lived and died in America / Good ol’ USA,” she sings on the latter tune. “Whole lotta red in that white and blue / History can’t be erased.”

Nor can it be silenced: This is one of “Cowboy Carter’s” central themes.

Through it all, Beyoncé continues to address the “Is she country enough?” debate head-on, the best way she knows how: in song.

“Used to say I spoke ‘Too country,’ ” she sings on show opener “Ameriican Requiem,” which she revisits at concert’s end. “And the rejection came, said ‘I wasn’t country ’nough. Said I wouldn’t saddle up.

“But if that ain’t country,” she asks, “tell me, what is?”

Contact Jason Bracelin at jbracelin@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0476. Follow @jasonbracelin76 on Instagram.