Exhibit focuses on the science behind gross-out animal behavior

Dung balls and hairballs and slime — oh my!

And don't forget the vomit slurpers and the bloodsuckers.

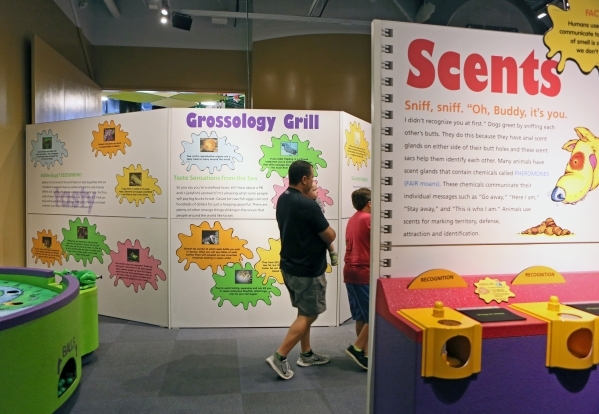

They're all part of the aptly named "Animal Grossology," the undeniably gross — yet utterly engrossing — touring exhibit at the Discovery Children's Museum through mid-April.

Based on the best-selling children's book by Sylvia Branzei (illustrated by Jack Keely), "Animal Grossology" introduces visitors to such animatronic creatures as slime-spewing Helga the hagfish and Malcolm, a rasta-accented parrot mascot who welcomes guests to the exhibit.

"Animals aren't the only gross ones," Malcolm says. "From our perspective, you human beings are pretty gross."

Indeed we are — as locals found out when a human-oriented "Grossology" tour played the old Lied Discovery Children's Museum about five years ago.

That exhibit had "sneezing, puking" and more, "but from a human aspect," recalls Denyce Tuller, marketing director of the current Discovery museum in Symphony Park. "It was tremendously popular."

Which seems to be the case with "Animal Grossology" as well.

On a recent weekday morning, multiple school buses disgorge hordes of grade-schoolers who descend on the exhibit. (The museum averages 250 to 300 field-trip students per day, according to Amber Heman, Discovery's science and nature education manager.)

Kids throng the Dung Ball Rally, where they play a video game to determine which dung beetle can climb a spherical pile of poop the fastest.

"Ha! I beat you!" one triumphant player proclaims. "I win!"

After celebrating her victory with a gleeful bounce, she catches sight of a factoid posted on the wall noting that, in parts of Texas cattle country, dung beetles remove 80 percent of the cow dung.

At the nearby Tapeworm Tug display, a student pulls a rope illustrating how long tapeworms can grow, while a classmate checks out what's under the display's adjacent toilet seat lid.

"Caca!" she giggles. "Ewww!"

But rather than being repelled, she peruses a diagram of a human intestine to see where tapeworms usually hang out.

And so it goes, as "Animal Grossology" pairs amusing animatronic animals with serious scientific facts.

"Science is just exploring the world around us," Heman observes. "And the world around us is gross."

Some of the exhibits in "Animal Grossology" are grosser than others, however.

"Party Poopers," set in a zoo, lets guests guess which excrement example goes with which animal, from rabbit to lion.

"Stupor Fly," by contrast, features a giant animatronic fly, perched atop a fake chocolate chip cookie. But what's that little puddle of liquid on the cookie?

Why, digestive acid, of course, which Mr. Fly regurgitates onto solid food to liquefy it so he can slurp it through his snout, more formally known as a proboscis.

As Mr. Fly informs his audiences, "I'm 10 million times more sensitive to taste than you humans." And, just in case you didn't know, "I'm tired of being swatted."

Step over to the nearby "Pellet Purge" exhibit and you'll learn how owls swallow their prey whole, then expel pellets containing skeletons of what they just ate. (There's a magnifying glass for kids to examine real bones — and a video game where they can test their ability to put the bones back together.)

"The Slime Game," by contrast, employs a TV game-show format (complete with your genial host, Mr. Slime) to determine which creature claims the all-time slime crown.

Visitors can vote for the exotic sea cucumber, the humble snail or the aforementioned hagfish Helga, who brags that "I slime so hard the water becomes like Jello to swim in — it's better than pepper spray.")

In reality, all three are super-slimy, but 11-year-old Robbie Sacco (visiting from Brimfield, Mass., with his family) votes for Helga.

"It was gross," he acknowledges, "but in a good way."

Speaking of good, "Slime Game" factoids point out that snail and slug slime may lead to a treatment for cystic fibrosis.

At "Underwater Adventure," some kids tumble down the slide-like expanse of an eel, while others investigate the submarine-like display.

Meanwhile, down on the farm, the "Chew-Chew Express" features a cutaway cow — and the four stomachs she uses to digest the cud she chomps for about nine hours a day.

"Eat, upchuck, chew," the exhibit explains. "Cows cannot digest food grasses any other way. If their stomachs were like humans, they would have a constant tummy ache."

Of course, all that cud-chewing creates a few side effects.

Sometimes, "the cow does release a little methane gas," Heman explains. "She lifts her tail and gives a toot. You've got to be careful."

The sound of a hearty bovine belch reminds Heman that cows burp too.

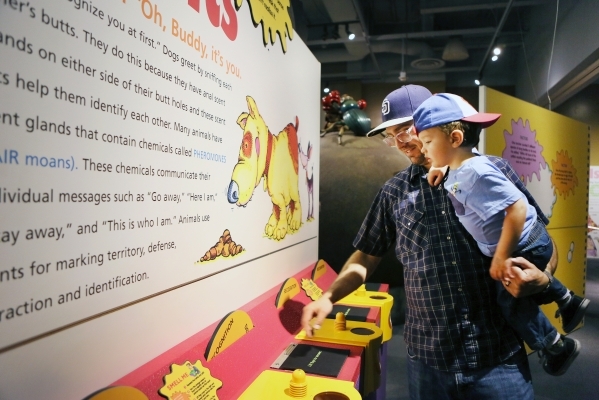

But back to smells — and the reasons animals emit them, from defense to attraction to recognition.

"I can smell that one just standing here," even without squeezing the "Sense the Scent's" scent bottle, says visitor John Lee, referring to a pungent skunk aroma.

"It is kind of gross," Las Vegan Tina Maloney says of "Animal Grossology" while her daughter Ava, who's almost 2, scampers between displays.

It's their second visit to the exhibit and "even me, I laugh," Maloney says. After all, "who doesn't like poop?"

— Read more from Carol Cling at reviewjournal.com. Contact her at ccling@reviewjournal.com and follow @CarolSCling on Twitter.