Approach museum exhibits with adventurousness and they’ll reward you, officials say

Here's the thing to remember: Going to a museum is supposed to be fun.

Yet, for many of us, visiting a museum can be an intimidating experience, especially if we're going to a museum that involves things - we're looking at you, art museums - that we don't know very much about.

To make museumgoing a bit more fun - particularly during the approaching dog days of summer, when spending an afternoon in an air-conditioned place around cool stuff is just the thing to keep antsy kids busy - we've asked local museum directors for tips on getting the most out of a museum visit.

First: Don't worry about what you don't know. Rather, visit a museum with the mind of an explorer and a simple openness to experiencing something new.

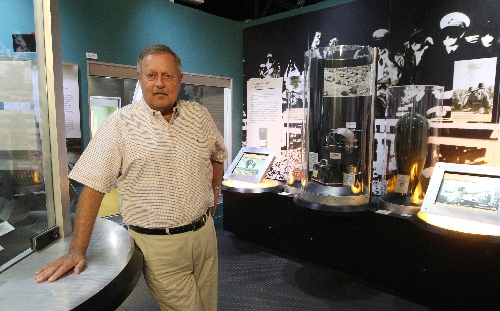

Allan Palmer, executive director of the National Atomic Testing Museum, 755 E. Flamingo Road, says visitors there enter with varying levels of knowledge about the Cold War, atomic energy and nuclear war. Some lived through it. Others read about it in history class. Others probably know absolutely nothing about it.

No problem, says Palmer, because even those who know little about the atomic age "almost universally, they come out going, 'Wow! That's so awesome.' "

Keep an open mind about what you might see. Palmer says visitors may come to the Atomic Testing Museum with an already formed opinion about nuclear weapons and the Cold War.

But, he says, "I think if people can kind of come in with an open mind and not rush it, and if they do not have an agenda, I think it will be a much better experience."

Don't worry about how to navigate a museum, fearing that your entire experience will somehow be ruined if you take a wrong turn and see the exhibits in the wrong order.

In a well-designed museum, exhibits will have a natural flow, says Mark Hall-Patton, Clark County museums director, who oversees the Clark County Museum at 1830 S. Boulder Highway in Henderson and the Howard W. Cannon Aviation Museum at McCarran International Airport.

"If it's well-designed, it shouldn't force you to think, 'Should I turn left or right?' It should be clear just by walking," Hall-Patton says.

Now, as you set off to check out exhibits, try to discern the theme or story line curators have devised.

A well-designed museum tells a story, and you should be getting the story without having to ask, Hall-Patton says.

"It should come through in the way the exhibits are put together and the labeling that is there," he says.

Marilyn Gillespie, executive director of the Las Vegas Natural History Museum at 900 Las Vegas Blvd. North, says she and her museum's educators are working on a Mayan exhibit, prompted by interest about Mayan doomsday predictions.

"So, we have to set out with a story line before we ever start constructing anything: What is the story we want to tell?" Gillespie says. "Then: What artifacts would we want to use to enhance the story, because, obviously, having something other than just the written word is so much more beneficial."

Conversely, there are times when "you have an artifact and you're going to build a whole story around that," Gillespie adds. But, even then, "definitely you'll know what the point is."

An exhibit's title may offer a clue. The Bellagio Gallery of Fine Art's current show is called "Claude Monet: Impressions of Light."

"If you don't know Monet is an Impressionist artist, you could just look at 'impressions of light' to see that these are artists that are talking about light, and color as well," says Tarissa Tiberti, the gallery's director.

How pieces are laid out also can provide clues about an exhibit's overall theme or story line.

In art museums, works often are laid out chronologically to illustrate the development of an artist's work, Tiberti notes, while, other times, exhibits may be designed to compare and contrast different styles of art with the goal of "creating a conversation."

An entire museum even can have a story line. For example, "for most of the stories we tell about animals throughout our museum, we know we want to talk about adaptation," says Gillespie of the Natural History Museum.

As you tour a museum and check out exhibits, you're taking in information. That information, Hall-Patton says, will help you decide how you're going to react to it.

"Are you going to accept it or not accept it, question it or not question it? That's up to you as a visitor," he says.

Visiting a museum is not taking a class, he adds; you don't get a test at the end.

Of course, how a visitor tours a museum will depend upon who's doing the touring. If an excited child is around, feel free to let the child take the lead, even if the route he or she leads you on may not be the most logical one to take.

"If you have a child, sometimes you have to rush through the rooms because, a lot of times, they're very excited to see what's around the corner," Gillespie says.

But don't worry. Indulge the child's enthusiasm now and just check out the rest of the exhibits later.

"At our museum, some children are very focused and they want to see the dinosaurs first," Gillespie says. "Then, they can backtrack and see some of the other things.

"But they're very focused on what their little agenda is, and parents have to be tolerant of that and let them do their own discovery."

Feel free to take advantage of instructional materials - maps, guides, explanatory texts, audio wands or podcasts, interactive displays, videos - the museum provides. But don't feel guilty if you don't take it all in, and feel free to ignore it all, too.

"There's obviously always a lot of signage in any museum, and it's never really possible to read everything," Gillespie says. "But I would just say that I think people should read as much as their enjoyment will allow them to."

Tiberti, meanwhile, likes audio aids - the Bellagio gallery offers visitors personal audio wands - offering commentary "written to tell the story. Sometimes I pick it up and listen to it and I'll learn something I never knew."

Hall-Patton, however, usually passes.

"Having spent my entire professional career in museums, I want to interact with the exhibit on my own and not listen to someone telling me about it," he says. "But that's my personal thing."

However, interactive displays and videos or movies can be a low-intimidation means of exploring a topic from a different perspective and, maybe, catching a breather, too.

At the Atomic Testing Museum, the Ground Zero Theater enables visitors to "sit through an atomic bomb test and experience what it was like to be there," Palmer says.

Take advantage of an often-overlooked museum resource: Docents and staff members.

"Don't ever feel bad about asking questions," Hall-Patton says.

Also check out instructional opportunities available to the public. The Bellagio gallery, for example, offers a docent tour at 2 p.m. daily during which guests can tour the gallery with a guide.

However, explore an exhibit or a museum as deeply or as cursorily as you wish and don't feel guilty if you're more interested in some exhibits than in others.

At the Atomic Testing Museum, casual observers "can go through in an hour," Palmer says, while "people who are really into it can spend more time there. Some people spend the whole day."

Don't feel compelled to take in everything in one visit. Trying to do so can lead to exhibit overload and make a visit more of a chore than an enjoyable afternoon out.

When visiting a museum with a child, take advantage of child-oriented materials a museum may offer.

The Bellagio gallery, for example, offers a children's guide that prompts children to think about what they see in a painting by asking such questions as whether the people in a painting look happy or sad.

When checking out exhibits, ask a child similar questions to help a child think about what he or she is seeing.

"There are such great stories of paleontologists around the world who say their inspiration to become paleontologists began in a museum," Gillespie says. "You just never know with children what sparks may be ignited by their visit."

Contact reporter John Przybys at jprzybys@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0280.