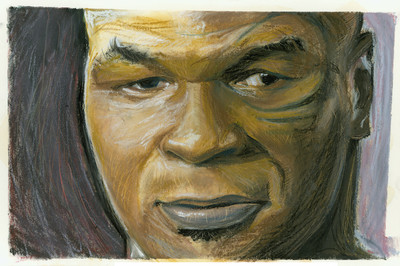

‘Tyson’ captures contradictory, compelling personality of boxer

On the surface, boxer Mike Tyson and mobster Bugsy Siegel would seem to have little in common.

Except, of course, for their notoriety, their Las Vegas connections -- and filmmaker James Toback.

Toback earned an Oscar nomination for his 1991 "Bugsy" screenplay, which explored Siegel's role in helping to create the Flamingo -- and the Las Vegas Strip.

And Toback's documentary portrait of "Tyson" -- which opens in Las Vegas today -- won an award at last year's Cannes film festival.

A mixture of new and archival footage, "Tyson" captures an endlessly contradictory, undeniably compelling personality.

"He was a front-page fighter, not a sports-page fighter," says Marc Ratner, who was executive director of the Nevada Athletic Commission during Tyson's heavyweight reign.

"There hasn't been a heavyweight since that time to intrigue people" in the same way, observes Ratner, who is now vice president of regulatory affairs for the Las Vegas-based Ultimate Fighting Championship.

In the documentary, Tyson reflects on everything from his troubled boyhood to his championship triumphs to his downfall(s) as convicted rapist, ear-biting fighter and cocaine-addicted ex-con.

As Tyson told Toback the first time he watched the documentary, " 'It's like a Greek tragedy -- the only problem is, I'm the subject.' "

It's a subject Toback knows well, having met -- and connected with -- the 19-year-old boxer after their initial meeting on the set of Toback's 1987 comedy "The Pick-up Artist."

The fighter and the filmmaker shared "a long night of conversation," discovering "a real sense of the other," along with a "closeness, a connection" that continued throughout Tyson's stormy life, Toback notes.

More than a decade after that initial meeting, Tyson played himself in Toback's controversial 1999 "Black and White," and "that movie gave him the idea" for a cinematic self-portrait.

"At that time, he was open to it," Toback recalls, "but I don't think he was in an ideal state" to reflect on the torturous turns his life had taken.

Instead, Toback waited until Tyson entered drug rehabilitation, at which point "he was in a completely raw state and totally ready" to take stock.

It didn't take much to get the process started -- except to start the camera rolling.

"He is so absolutely incapable of saying anything other than what's coming directly out of his mind," Toback says. Assuming Tyson's interested in talking, that is.

As for the link between his two Vegas-related movies, both Siegel and Tyson "are what Tyson describes as extremists by nature," Toback says. "They invent their own morality," and in the process "defied the popular notion" of acceptable behavior.

Despite -- and due to -- such conflicts, Tyson remains a fascinating figure, Ratner acknowledges.

"Boxing fans are intrigued by him," he says. "Even to this moment, when he walks into a fight, he draws a reaction like no other fighter."

Which hardly seems surprising, in Toback's view. Considering "the incendiary nature of his life," the filmmaker says, Tyson "invites controversy, attention and excitement."

Contact movie critic Carol Cling at ccling@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0272.