Musician quit ‘best job in the world’ to start record label

Allan Carter’s voice is a pine cone in a forest of noise.

From a hot room on a cold night, he struggles to explain why he cashed in his 401(k) three years ago to start a record label at a time when record labels have become musical penny stocks, the business equivalent of tossing a handful of magic beans out the window with little promise of a beanstalk.

He’s not laboring with his words because he has any regrets or because it’s difficult to rationalize his decision on a purely financial level — some decisions are beyond cognition, exempt from logic; they come, instead, from the gut.

It’s not monetary concerns, then, that bedevil Carter at the moment, it’s the happy racket that consumes the Double Down Saloon, swallowing the packed, stuffy space in the pandemonium of a Friday night, the onset of the weekend goosing the spirits of those who fill the crowded bar.

Ironically, or perhaps appropriately, the din becomes amplified at one point by Vegas punks The Gashers, a Molotov cocktail of sound who are one of the bands signed to Carter’s Squidhat Records.

They roar from the jukebox like some clawed animal trying to scratch its way free from confinement.

This may be the worst place in the city to attempt to have a conversation right about now.

The thing is, though, Carter needs to be here.

It was on a bar stool in this very room that the idea for Squidhat was born.

Since then, the label has signed a dozen acts, including a who’s who of Vegas punk bands, secured national and international distribution, put out 13 releases available in stores from Omaha, Neb., to London and begun to make real headway as an enduring label with marketing muscle in a city historically short on them.

Squidhat has helped bands book tours across the country and get on the radio in cities such as Montreal and Boston.

It’s become a much-needed incubator for local talent, a support system for working-class musicians with day jobs.

Every scene needs an infrastructure, and Carter is helping provide it.

In doing so, he’s losing money and losing sleep.

But he’s gaining momentum.

On this chilly January evening at the Double Down, Squidhat is hosting its second-anniversary showcase, a two-day event where various unsigned Vegas bands will perform in hopes of landing a record deal.

This is where the next Squidhat acts will come from, and fittingly so.

It’s here that the story of the label begins.

And so Carter heads outside to tell it.

FROM WINE TO PUNK ROCK

His words are the opposite of the crisp night air: heated.

Allan Carter doesn’t just tell a story, he animates it with his eyes, which flash in unison with a frequent smile in a manner suggestive of a strobe light’s steady pulse.

Imagine the moisture wrung from a wet sponge: that’s how thoughts, ideas, observations, life lessons and enthusiasm — endless enthusiasm — flow out of him all at once.

Currently, he’s talking about what brought him here, pausing only to greet the Double Down soundman.

“I had the best job in the world,” says Carter, a stocky guy with numerous tattoos, including one of his favorite artist, Prince. “I could have coasted into the sunset and retired. And I woke up one day and said, ‘I’m not happy. I’m not doing anything but making old white people rich,’ which I’ve done my whole life. So I quit my job, moved to Las Vegas and floated the label. That first year was $75,000, and we had nothing to sell.”

Carter is a veteran musician who’s played drums for 30 years, from funk acts in his native Baltimore to punk bands in Portland, Ore.

But selling things is what he’s really good at.

He’s spent much of his adult life in the wine business, heading sales and marketing at Domaine Serene in Oregon before relocating to Vegas. Presently, he’s the brand manager for fine wine at Southern Wine &Spirits.

Carter developed a taste for wine years ago while traveling the world as a “product evangelist” for a tech firm, selling mobile wireless applications in the early ’90s. In Japan, he learned the value of being able to pair the proper wine with dinner.

“At night, they’d take you out drinking and see what you were made of. That’s where the business was getting done,” he says. “I figured out very early on that if you could get a bottle of wine that went with what everybody else was eating, they loved that and they listened to everything you had to say. So I started reading about wine and food pairings.”

It’s this same kind of hands-on, self-taught method of figuring out what works and what doesn’t that Carter is applying to running a record label.

“Good marketing takes a good product, puts it into a message that the target demographic can understand and then finds that demographic,” he says. “I’ve sold software. I’ve sold wine. Now I sell music.”

A LABEL IS BORN

The band that inspired Allan Carter to start a record label is performing beneath a ceiling fan the size of a helicopter turret.

“I need one of those for my backyard,” The Gashers singer-guitarist Jason Hansen quips, gazing up at the thing, which sends assorted hockey pennants fluttering at the Las Vegas Event Arena.

Still, the room is hot and smells like teen spirit.

The Gashers play on a small stage in the middle of a roller hockey rink, where a few dozen young people and assorted parents watch them perform inside a ring of police tape.

A girl in fishnets and another in a cheetah-print skirt spin themselves in circles as the band plays, eventually falling to the ground in a tangle of limbs. A dad with gray in his beard watches bemusedly. Assorted moms eat nachos in the bleachers outside the rink. A girl with the unsteady legs of a new-born colt rollerblades around the makeshift barrier.

The Gashers are one of 18 bands performing at this all-ages, all-day punk rock skate fest.

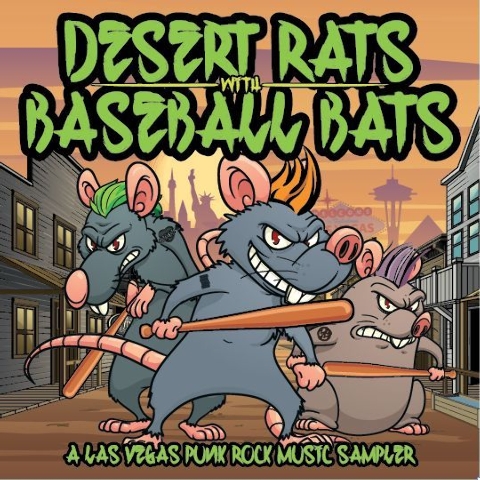

The event is partially sponsored by Squidhat and doubles as a release party for the label’s “Desert Rats with Baseball Bats 2” compilation.

The Gashers are one of the old-school acts on the bill, formed from members of similarly gruff, no-nonsense punks the Peccadilloes. It was this bunch, along with female punks The Dirty Panties, that made Carter want to start a label. They were the first two bands he signed.

“To be honest, I was a little shocked,” says Hansen, a mohawked, gravel-voiced punk lifer, working on a beer after his band had finished. “We never got into playing music to get famous or get rich. We all do it just for fun. So it’s great to have support.”

Carter saw both The Gashers and The Dirty Panties numerous times at the Double Down, which he began frequenting while on tour with Portland punks Attack Ships on Fire.

After watching the Panties play one night, Carter approached them to buy some merch — a T-shirt, a sticker, a CD, something.

“Apparently we laughed at him and said, ‘We don’t have CDs, we don’t have money, we don’t get paid to play,’” recalls Panties bassist Michele “Lil’ Moe” Meyer.

Carter saw a void: Let the bands focus on their music; he’d market it and help out on the business end.

The idea for Squidhat Records was born.

Next, he recruited Attack Ships on Fire band mate Mike Bell, an accountant, to help with the books and serve as vice president.

“He announced the idea one night at band practice,” Bell recalls. “He just said, ‘I’m starting a record label based in Las Vegas. I’m going to call it Squidhat Records. That’s my retirement fund.’ And we all just kind of laughed.”

Carter would complete the Squidhat management team with Stephen Fahlsing, an L.A.-based musician and producer who runs Bonfire Recording Studios, where numerous Squidhat acts would later record albums.

First, though, Carter had to persuade bands to work with him, this out-of-towner with no experience running a label.

Carter turned to Double Down owner P. Moss to introduce him to The Gashers and The Dirty Panties and vouch for his intentions.

“It was hard,” Moss recalls of overcoming the initial skepticism that each group had of being approached by a startup label. “There have been guys coming to this town promising the world since I started doing my (thing), and they’re all full of (it), to the point where everybody in this town knows that. So, here’s this dude that nobody knows, he’s starting a label, he wants to sign you, why would he not be the same in their eyes? But he wasn’t. It didn’t take him long to prove that he was for real.”

Eventually, Carter won both bands’ trust.

And then he lost $30,000 in expenses during Squidhat’s first year.

In 2013, those losses dipped to $2,500.

He hopes to break even this year.

YOUNG GUNS BLAZE A PATH

The big dude with the ice-pick sharp voice spends as much time off stage as on it.

“I want to kill you ... dead!” singer Jesse “Anarchy” Young howls as assorted crowd members bounce off him like he was coated in rubber.

Back at the Las Vegas Event Arena, coed punk outfit Sounds of Threat is playing. A younger band, it performs as if under attack, returning fire with fast, fierce songs that detonate like a string of fireworks exploding one right after the next.

A circle pit forms. The rapid movement mimics the surging momentum of the sound, threatening the life of the P.A.

A few weeks before the show in question, three-fifths of the group meets in Carter’s living room, where he approaches the members about working with Squidhat after the band impressed him and his partners.

“We really thought your set was incredible,” he says. “If we can find a way to get that energy on a record, you’re lightning in a bottle.”

Carter begins by handing each band member a sheet of paper titled “What We Expect from Our Artists” that’s lined with bullet points.

“This is probably the most important thing that I give anyone,” he says.

It’s a tip sheet with practical advice for musicians to get the most out of their band.

It’s dotted with bold-faced headings like “No one should care more about your music than you,” “Promote your band at every turn” and, toward the bottom of the page, “We can’t make you famous.”

“Only you can make you famous,” Carter tells the band. “But I can get you into the world.”

He gives them the standard artist agreement that Squidhat offers prospective signees.

“Look at it, read it, have other people look at it,” he advises. “Look for all the loopholes where we try to Warner Bros. you and own your music forever and ruin your lives.”

The terms are for one record, with Squidhat owning the album masters for five years. The label takes a chunk of publishing, and in turn, profits are split 50-50 between the band and Squidhat after expenses are recouped.

Carter tells the threesome that if they get approached by a bigger label, he won’t stand in their way, citing powerhouse punk indie Epitaph Records as an example.

“If Epitaph called you and said, ‘We love you, we want you’ and you’re under contract to me, I will shake your hand and let you go,” he says. “But, I do retain the masters to our first album, so that when your second album is huge, people will come and buy the first album from me.”

Squidhat’s best chance for financial success may be finding a band promising enough to graduate to a bigger label, the same way Nirvana’s departure from Sub Pop to major label Geffen ended up saving the former from bankruptcy when “Nevermind” became a hit and millions of new Nirvana fans sought out the group’s debut record from Sub Pop.

Carter’s pitch to Sounds of Threat isn’t a soft sell.

“To be perfectly blunt, we think that you’ve got some developing to do,” he says. “I think that the energy is there, but when you’re making your album, you’ve got to really focus on that musicality.”

Carter knows that a band like this could play an important role in the future of the label.

Up to this point, Squidhat has signed mostly established, veteran bands.

Sounds of Threat has been around for five years, but it’s young and hungry and still making a name for itself — albeit quickly.

Best of all, the group is willing and able to tour.

“I really think that we are the type of band that really wants to get out there and not be a band that plays in Vegas,” says Young, a sizable man with chin piercings. “I feel like all of us want something more to see what this band can do.”

Carter emphasizes the importance of the band hitting the road — and hitting it hard.

“You don’t need me to get people to come see you in Las Vegas. It’s the rest of the world,” he says. “When we put (an album) out there and all of a sudden, for some reason, it’s a big deal in Lincoln, Neb., you need to go to Lincoln, Neb.”

He tells them that he’s willing to put himself on the line financially.

“If I spend five grand on you, it’s not a loan. It’s an investment. The risk is mine,” Carter says. “It’s what I believe in.”

Weeks later, they sign the deal.

MAKING THE SCENE

“This is how scenes happen, what we’ve got going on right now,” says the man high on the list of Las Vegas’ most excitable musicians.

Cody Leavitt sits in the near-dark of Frankie’s Tiki Room, though sitting is not really his thing. The guy is a blur of activity, a fixture at local shows who plays in numerous projects and who seems to know just about anyone in a band in Las Vegas.

“I’m a professional middle man,” he says, his words coming as fast as a boxer’s hands.

Leavitt’s main band, rootsy Henderson barroom rockers The People’s Whiskey, is one of Squidhat’s best-selling acts.

On this night, he’s flanked by a couple of his label mates, Lizzy Minx, who fronts synth popsters Pet Tigers, and Andy Harrison, founder of punk band New Cold War.

Not only are they all signed to Squidhat, they work for the label as well.

Minx, an outgoing blonde who could find a way to chat up a turnip, does publicity, naturally.

“Anything I believe in, I want to talk about,” she says. “If I’m excited about something, and I want to sell it, I will sell it to anybody.”

Harrison, a skilled graphic designer who works with the UFC among others, does album art and band fliers.

Leavitt books shows, mentors bands and serves as a conduit between Squidhat and younger groups.

“I kind of do farm-team research,” he says. “I go out there and prep the kids, work with them. It’s not just signing Las Vegas bands, it’s helping develop Las Vegas bands, develop the scene.”

Their participation in the running of the label brings to mind Seattle super-indie Sub Pop Records, which employed members of its bands to work in the office and warehouse as the label made a name for itself in the early ’90s.

It not only further entrenches Squidhat in the local scene, it helps foster a sense of community, which the best scenes are built upon.

“To me, Squidhat is helping us all get along, even with bands we didn’t think we liked,” Harrison says. “It’s a family, and that’s what feels cool about it.”

It doesn’t end with these three: Guilty by Association frontman Mike Janoff, who’s done years of touring, helps bands with contacts when they want to play out of town. The Gashers’ Jason Hansen and singer-drummer wife Sandra have a rehearsal space in their home dubbed The Thirsty Clover that has been a gathering point for Squidhat bands.

“We all have this goal, as one team, we want to grow Squidhat,” says Rich Castro, drummer for Surrounded by Thieves, which is signed to the label.

Leavitt, in particular, takes a hands-on approach to building ties between Squidhat and the local scene.

He was instrumental in putting together the “Desert Rats with Baseball Bats 2” compilation, which could be a game changer for the label in more ways than one.

Not only did it see Squidhat working with a younger crop of bands who could figure into the label’s future, but it was the label’s first vinyl release.

It’s been Squidhat’s biggest success yet.

VINYL DREAMS, CD NIGHTMARES

The storm clouds hovering above the record industry contain no silver.

But they may be lined with vinyl.

The bad news kept coming for the music business in 2013: CD sales were down another 14 percent, and for the first time since the iTunes store opened in 2003, the sale of digital tracks dropped as well, falling nearly 6 percent.

Cue the sad trombones.

But there was one bright spot: vinyl record sales increased a whopping 32 percent, reaching their highest levels since the advent of Soundscan in 1991.

Squidhat learned the value of vinyl in April when it released “Desert Rats with Baseball Bats 2,” its first LP, which immediately became a top seller.

“They’ve tripled our biggest distribution order so far,” Squidhat vice president Bell says. “This definitely feels like a big one.”

Other Squidhat bands are getting in on the action.

The Quitters recently issued their latest album, “Contributing to Erosion,” on blue vinyl, and it, too, could bode well for the label’s fortunes. Not only is it among the best albums Squidhat has put out, but its first single, “Hipster,” has been gaining traction on radio stations around the country, from Phoenix to St. Louis.

“Nowadays, if you’re going to sell anything that’s a physical copy of your music, it’s going to be vinyl, because those are for the audiophiles,” Quitters drummer Micah Malcolm says.

Vinyl in and of itself isn’t especially lucrative.

To get a $13.99 list price for one of his band’s records in stores, Carter has to sell the album to the distributor for $6.75. Records cost around $5 each to produce; CDs can be done for around $1, depending on the size of the order.

So Squidhat makes a $1.75 for each vinyl album sold, and this comes after a six-month wait to see if any of the albums were returned by retail outlets after going unsold.

Still, they’re selling, and that’s something.

Carter’s plan moving forward is to have bands record full-length albums, then issue four or so songs on a 7-inch vinyl record that includes a digital download card for access to the full album.

“We’re not going to sell a million records, so I’m not going to make any money,” Carter says. “But, if people buy the 7-inches for four, five, six bands, then I’ll start to make enough revenue.”

This is the only way for a small label like Squidhat to survive: ingenuity and flexibility.

“You have to be agile,” Fahlsing says. “We started with CDs, but we’re realizing that’s probably not the best course of action, so we’re making a lot more vinyl. But that could change tomorrow.”

Of course, vinyl sales aren’t going to suddenly make Squidhat flush with cash, but they could be an important boost at a crucial time.

This is the last year that Carter can write off losses from the company on his taxes, and he needs the label to start paying for itself.

“Next year, we’ve got to be profitable,” he says.

Back at the Double Down, Carter extends an invitation to visit Squidhat World Headquarters (his house on the outskirts of downtown).

“You can see my wall of gold records,” he jokes of his home office, where he works on Squidhat business most nights until 1 a.m. after his day job.

Instead of gold records, the walls are lined with album art from various Squidhat releases.

This is Carter’s real payoff, putting out records he digs.

It may be his only payoff.

He seems content with that.

“It’s a legacy thing,” he says. “I’m now responsible for my grandkids’ classic rock. What are we leaving them?”

Carter will keep answering this question, album by album, for as long as he’s able.

“If I can get 20 or 30 or 50 records that I’m proud of out in the world, then they’re in the zeitgeist, they’re out there forever,” he says. “We’re not going to get rich — I hope one or two or more of our bands break. But 20 years from now, if people come looking for the Vegas music scene or explore it, we’ll be a part of that.

“And that’s not going to change.”

He let’s the thought sink in.

And then, there’s that grin.

“It’s calculated luck,” he says. “That’s all music is.”

Contact reporter Jason Bracelin at jbracelin@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0476. Follow @JasonBracelin on Twitter.