Bop Art

Jagged orange lightening bolts frame a box of rainbow swirls beneath a diamond-shaped prism inside a bright yellow square angling into a tangle of colored streamers.

Can you see the music?

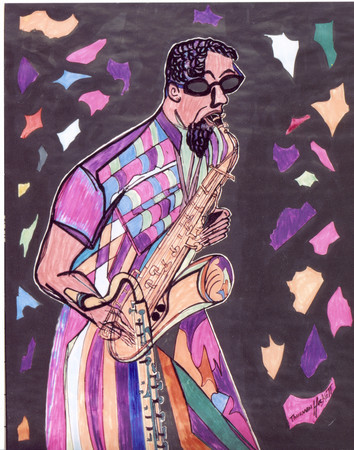

Showers of confetti fall and gather around the legs of an elegantly suited musician, the curvature of an instrument snaking down and sweeping away from his body into the bell of a saxophone protruding naturally from his body like an extra limb.

Can you see the man making the music?

Jazz, created for the ears and interpreted for the eyes by an artist transforming sound into scenery and sketching the icons from whom they flow.

"It's abstract, but with a heavy flavor of realism," says Las Vegas artist and ex-sax man Thurman Hackett. "I put abstract in my work because that's what these guys were playing, abstract music. They didn't play a straight line or abide by all the rules that were set down. They used that, but they absorbed it into their own renditions and changed it."

Circling the gallery at the West Las Vegas Arts Center are pieces of his "Historical Journey Into Jazz" collection -- some not merely historic, but hallucinogenic -- displayed through December.

"I paint lots of things but jazz is my favorite because I just fit right in. I can put myself into the image and the mannerisms of these men and women who were in the music. I was in the clubs and saw how they performed."

Jazzy giants -- Lester Young (the aforementioned horn-blower in the piece titled "Complex Patterns of Jazz"), Charles Mingus, Ron Carter, Cannonball Adderley, Eric Dolphy, Betty Carter, Archie Shepp, Don Cherry and Duke Ellington, among them -- distinguish the show produced by Hackett, author of a companion book explaining their legacies not only as performers, but as artists.

"These men onstage, they were very serious onstage and that's what I try to bring out in my paintings," says Hackett, a retired interior designer, originally from Fresno, Calif., who played alto and tenor sax around L.A. in the '60s, before asthma interfered with his abilities. Yet his passion found another artistic outlet.

"These men were not very flamboyant -- there were a few, like Dizzy Gillespie, but most were almost like businessmen, practicing their craft onstage."

Boldly colored in an array of styles, this jazz journey jumps from legend to legend (though minus such greats as Gillespie, Miles Davis and Charlie "Yardbird" Parker, whose portraits Hackett sold to private buyers).

"Lady Day," Hackett's rendering of Billie Holiday, the matron saint of jazz-blues singers, is a straightforward profile of the artist in thoughtful repose, two white flowers gracing her hair, but without any allusions to the fragile, emotionally tortured side of this tragic figure. In an upbeat portrait, "Rubato Singer" casts vocalist Betty Carter in robust brush strokes, wearing a mischievous little smile, a finger to her lips.

"When she got onstage," Hackett says, "she made the music talk."

Pain that sometimes fueled the music is suggested in "Prez," an impression of Lester Young, one side of his face a Picasso-like abstraction suggesting the turmoil he endured. "Lester Young went through a lot, he got damaged pretty bad psychologically, especially when he went into the army. He was abused and he never got over it."

In "Jazz Virtuosity," saxophonist Eric Dolphy is king of the cool cats, wearing the hipster accoutrements of dark shades and goatee and resplendent in a dazzling cloak reminiscent of Joseph's amazing technicolor dreamcoat. Purple, blue and white leaves fall around him, as if they're vibrant sax riffs. "He was unique," Hackett says. "He was avant-garde, but he organized it. He didn't want to get away from structure completely, he wanted his audience to understand it."

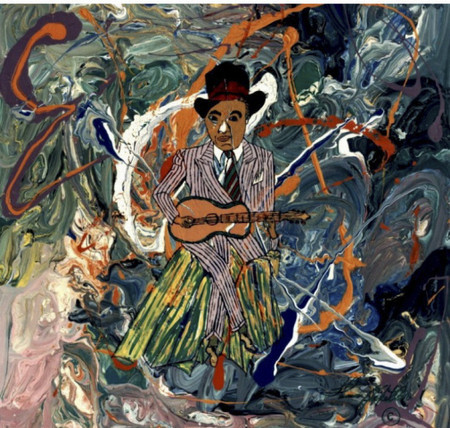

"The Jazzman of Bebop Blues" reveals saxophonist Cannonball Adderley, portly and serene, simply sitting and performing. But "Jazz on Tenth Avenue" features a frenzied amalgam of colors and a jutting one-way city sign, signaling the energy of street musicians. "Foundation of the Blues" captures Delta blues pioneer Robert Johnson in a dapper suit, guitar in hand, the central focus against a curling mass of rainbow hues for a look evocative of a legendary painter.

"The technique is really taken from Jackson Pollock," Hackett says. "But I don't do my work on the floor."

Further evidence of stylistic dexterity is found in "Jazzman of Avant-Garde," depicting saxophonist David Murray -- a cousin of Hackett's -- with a caricaturish, Al Hirschfeld-esque flair. Conversely, "Blues Beginning," set against a pastel splatter of blue and pink, finds two rural children at the feet of an older one, harmonica to his lips. "I took that from an old cutout from a 1946 magazine," Hackett says. "They were tapping their feet and snapping their fingers, really showing how the blues began."

Channeling aural pleasures into visual treasures, this devotee of America's native music has turned all that jazz into all that art.

Contact reporter Steve Bornfeld at sbornfeld@ reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0256.

Preview

"Historical Journey Into Jazz" exhibit

11 a.m.-9 p.m. Tuesdays-Fridays, 10 a.m.-6 p.m. Saturdays (through Dec. 31)

West Las Vegas Arts Center, 947 W. Lake Mead Blvd.

Free (229-4800)