Atomic Testing Museum brings backstory to bygone era’s lifestyle

It was during his very first stroll through the National Atomic Testing Museum that Allan Palmer saw something that left him, he admits, “stunned.”

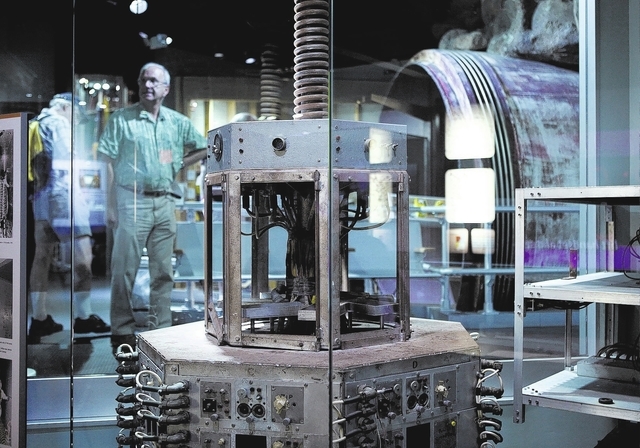

There, among the museum’s exhibits, was a deactivated B61 bomb.

That it was there wasn’t surprising. A museum devoted to chronicling the development of the Nevada Test Site and the history of nuclear testing in Nevada would be a natural place to find a non-working model of a tactical nuclear weapon from the ’60s and ’70s.

But Palmer knew that particular piece of Cold War ordnance well. During the Vietnam War, he flew F4 Phantom fighter-bombers outfitted with that very thermonuclear device, and if history ever were to take a nasty turn, Palmer — then an Air Force pilot stationed in Japan — would be called upon to deliver it, on what likely would be a one-way trip, to a target somewhere in the Soviet Union, China or North Korea.

“It was top secret,” Palmer says. “You couldn’t describe it to anybody, you couldn’t photograph it. And, now, it’s sitting on the floor and people are walking right by it.

“It was one of those moments in life where you do a double take.”

It’s just that sort of firsthand familiarity with the realities of the Cold War that makes Palmer the perfect person to serve as CEO and executive director of the National Atomic Testing Museum, 755 E. Flamingo Road.

Palmer also brings to the position years of experience gained from running museums after his retirement from 20 years of active military service. But, most of all, Palmer — a low-key, affable guy with a wry sense of humor and the innate ability to tell a good story — is a knowledgeable tour guide who can make history, be it the world political landscape after World War II or the weirdness of Area 51, come alive.

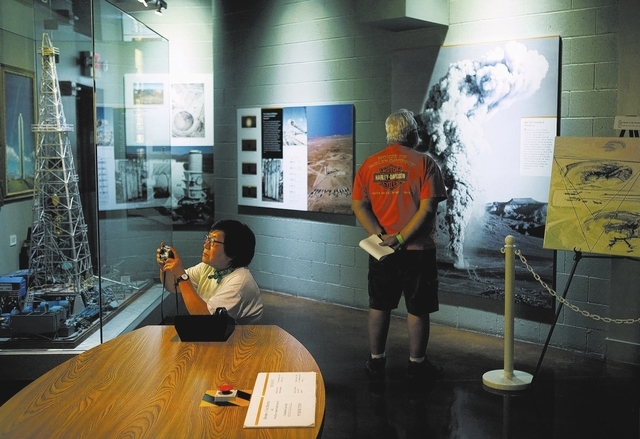

The National Atomic Testing Museum is Nevada’s only national museum and an affiliate of the Smithsonian Institution. Touring it is a fascinating, occasionally nostalgic, experience for anybody who lived through the Cold War, that post-World War II period that gave Americans bomb shelters, duck-and-cover drills and end-of-the-world movies that don’t involve zombies.

Members of that particular generation do make up a significant portion of museum visitors, Palmer says. But, he adds, younger people who know of the time only through history books and their parents’ memories also invariably find the museum interesting.

By the way, another sizable demographic: Tourists from Japan, the only country in the world that has been the target of a wartime nuclear attack.

Why? “Because they don’t teach it in their country,” Palmer says. “It’s not a chapter of their history they’re very proud of, so they don’t cover it as much in school.

“So when they come to the United States, whether it’s the museum at Pearl Harbor” — where Palmer worked before coming to Las Vegas three years ago — “or here … they’re thirsty for information. They’re big buyers of books and DVDs, because they just don’t know that history.”

Palmer recalls one guest, a labor attorney from California in her 60s, who came to Las Vegas with her husband. Noticing that the museum is a Smithsonian affiliate, she stopped in, “not knowing what it was.”

“She said she was fascinated,” Palmer says. “She spent all afternoon here and didn’t finish, and came back the next day. She said, ‘I lived through that period, but I didn’t really understand it and didn’t understand all of the background of what was done with the testing.’ ”

“Every week we see people leaving comments: ‘Wow, what a wonderful story. I was amazed. I didn’t know,’ ” Palmer says. “It’s an amazing piece of history to a lot of newer generations.”

The National Atomic Testing Museum opened in 2005 with the mission of exploring development of the Nevada Test Site — now called the Nevada National Security Site — and the history of nuclear testing in Nevada.

But “in a larger sense, it’s about the Cold War and how we came, almost, to the brink of destruction,” Palmer says. “The real underlying message here in the museum is, there are some really useful lessons that we learned during that time that ought to serve us going into the future and as we deal with an increasingly nuclear world.”

Besides examining the scientific, political and military aspects of the Cold War and nuclear testing both here and at other locations around the country, the museum also looks at the era through a societal and pop culture lens.

Take, for instance, the display devoted to “atomic” products, from comic book covers to toys to cereal boxes to drink menus, that recalls just how enthusiastically — and, in retrospect, how naively — Americans embraced the Atomic Age.

Then, on the flip side of the coin, check out the posters of B-movies that feature various atom-spawned monsters.

“All of those old horror movies — ‘Them’ and ‘Godzilla’ — all developed around the same time, in the mid-to late-’50s,” Palmer says. “That’s when we were doing all the testing out there in the desert.”

The museum’s examination of the Cold War era also can be seen in its popular Area 51 exhibit (a temporary exhibit that Palmer says now has been extended into 2014) that looks at the not-so-secret government installation where much of the United States’ Cold War aviation technology was developed.

The goal, Palmer says, is to “balance it a little bit as a way to bring the more nontraditional (visitor) into the museum.”

Palmer, a San Francisco native, is third-generation Air Force — his dad was an Army Air Corps officer and his grandfather one of the corps’ earliest aviators — and grew up on bases around the United States and the world.

But he hadn’t planned on pursuing a military career himself.

“I was headed for medical school out of college,” Palmer says. “Then Vietnam intervened and I was about to be drafted.”

He joined the Air Force and flew more than 100 combat missions in EB-66 (tactical electronic warfare) aircraft and 58 missions in F-4C Phantom II aircraft during the Vietnam War. He also flew the first F-4 Wild Weasel combat mission over North Vietnam, taking out surface-to-air missile and anti-aircraft artillery installations.

Yet, Palmer jokingly calls himself a “draft dodger” in that he joined the Air Force rather than be drafted into the Army.

“I thought that was pretty neat,” he says. “So, two years later, I found myself getting shot at anyway, just in the air instead of a foxhole.”

It was during that period, from 1969 to about 1975, that Palmer also flew F4 fighter-bombers outfitted with B61 nuclear bombs.

“The world was a pretty spooky place then,” he says. “A lot was going on and everybody was on an alert posture.”

In 1975, Palmer left the Air Force and was transferred into the Navy where, based on the USS Constellation, he flew the F-14A Tomcat. An interagency transfer was “very, very rare, particularly for an active duty regular officer,” he says. “I was a line officer in the Air Force and, at the stroke of midnight, I was Navy.”

Before retiring from active duty in 1986, Palmer also served in Washington, D.C., and at Pearl Harbor. His combat decorations include the Silver Star for gallantry in action, four Distinguished Flying Crosses with the Combat V for heroism and 11 Air Medals.

After retiring from the Navy, Palmer worked for a hospital corporation and airlines before entering museum management. He has served as executive director of the San Diego Air and Space Museum and was founding executive director and CEO of the Pacific Aviation Museum-Pearl Harbor.

Now, at the National Atomic Testing Museum, Palmer’s mission is to make a pivotal period in America’s, and the world’s, history relevant to visitors of today.

“My sense is, most people know about setting off the bombs here, but they don’t know why and don’t know the backstory of the political struggle of the Cold War and the danger with the Soviets,” he says. “I think it’s one of those stories that I don’t think people can appreciate until they get into it a little bit.”

And, as certainly also is true in Area 51’s case, truth can be much stranger than fiction.

“You couldn’t make a more convoluted, difficult story than the Cold War in all of the things that emanated from it,” Palmer says.

Take, for instance, the Las Vegas department store owner who donated mannequins for use in early above-ground nuclear bomb tests at the test site.

“If they weren’t totally destroyed, he’d put them back in the store, put clothing on them and they were back on display,” Palmer says.

Does Palmer ever hear criticism that the museum’s narrative is, perhaps, a bit too rose-colored?

“There are some people — not a great many, but there are some — who say, ‘You’re a mouthpiece for the government’ ” Palmer says. “We, on the other hand, want people to know we’re kind of the honest brokers here.

“We’re not the government. I don’t work for the government. We are an independent, nonprofit organization and we are affiliated with the Smithsonian, so we have a public trust to tell the story the straightest way we can.”

Contact reporter John Przybys at jprzybys@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0280.