Advance Romance

Broads, dames, dolls, vixens, sirens, skirts, gals, chicks, babes ... women.

Over six decades, the heroines and heartbreakers sashaying across the covers of Harlequin novels -- thighs flashing, bosoms beckoning, lips pouting, lingerie put on to be taken off, and fast! -- have evolved into today's strong, sexually sophisticated women who just as easily objectify the male of the species.

And yet ...

What broads, babes, dames and dolls they were -- breasts, lips, legs and all.

"Harlequin began as a publisher of books for both men and women, so a lot were meant to engage the male reader," says Elizabeth Semmelhack, curator of "The Heart of a Woman: Harlequin Cover Art 1949-2009," exhibiting more than 100 original works at Paris Las Vegas. "It's a really interesting window into exactly when women began to agitate in their own hearts for social change. What better place to look for moments of social change than at things that are mass produced? You find these things revealed in these covers."

Sociologically intriguing as well as artistically titillating, "Harlequin" enlarges many of the pieces normally appreciated as compact, 4-by-6-inch covers inviting readers inside those literary bodice-rippers -- yes, pectoral poster boy Fabio makes an appearance here -- and the effect is alluring for both sexes.

"When I stopped by the exhibit, I found it very intriguing the number of men who were really interested," says Harlequin spokesperson Michelle Renaud. "Men do read our books and they do appreciate the artwork, especially of the early books."

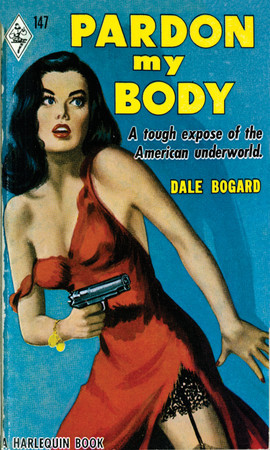

Though long synonymous with female-targeted tales of romance, Harlequin's initial mysteries and thrillers relied on pulpy artwork to leave guys salivating, so "Harlequin" begins by serving up cheesecake.

A parade of comely cuties includes "Anna: She Lived Like a Wicked Little Animal," with a voluptuous Jane Russell look-alike kneeling on a bed of hay. "Virgin with Butterflies" features a dewy ingenue (not too dewy -- note the flash of gam) surrounded in a surreal, suggestive tableau by men's faces inserted between butterfly wings, fluttering around her. And phallic-minded "Yellow Snake" paints a bearded stud and a frightened (but foxy) female confronting a rising reptile, a wink-wink reference to, shall we say, uncoiling sexuality.

However, the sex-drenched depictions also could turn from flattering to frightening the male ego: "You Never Know With Women" portrays a dangerous blonde concealing a blood-soaked knife while a man appears terrified in the background. "Pardon My Body" presents a gorgeous gun-toting brunette in a scarlet dress, one strap off her shoulder, one of her assets threatening to pull a Janet Jackson. Then there's (yikes!) "The Valley of Silent Men," wherein a woman unleashes a blast of gunfire aimed at a gaggle of cowering Canadian Mounties.

"You have these sirens of seduction on the covers, very aggressive women with tools of destruction in their hands," Semmelhack says. "It's interesting that it's appealing to the male audience, these strong, domineering women."

Divided into decades and eras, "Harlequin" heats up into a colorful cauldron of characters in bright, pop-art boldness -- gamblers, cowboys, rogues and tuxedoed playboys luring and flirting with damsels both delicate and daring, in and out of distress, against settings from street corner cafes to foreboding jungles to the sweltering tropics to the Taj Mahal. Epic gallantry emerges, such as in "Rebel Yell," as a cowboy galloping on horseback sweeps a woman up onto the saddle as they outrun a male tormentor.

Progressing into the '60s and '70s, a shift toward gender politics culturally alters the artwork as men drift from dominance. "In the middle of the women's movement, men disappear almost completely from the cover," Semmelhack says of depictions stressing women's mounting accomplishments, pictured solo and in scenarios as doctors, nurses, stewardesses and other professional roles.

Running through the '80s and '90s right into the new century, photography assumes a larger presence on Harlequin covers, reversing the ogling of women as men are cast as eye candy -- though no more subtly than the '50s aesthetic. Consider "Flyboy," in which a sculpted piece of beefcake -- aka, flyboy -- strips off his flight overalls as sizable rockets curve upward behind him.

"One piece has a man where you don't see his face, only his body," Semmelhack says. "You don't even care what he looks like anymore. You don't know his job or socio-economic standing. All you know is he has a really nice six-pack."

Ah, romance.

Contact reporter Steve Bornfeld at sbornfeld@ reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0256.

Preview

"The Heart of a Woman: Harlequin Cover Art 1949-2009"

10 a.m.-10 p.m. daily

Paris Gallerie at Paris Las Vegas, 3655 Las Vegas Blvd. South

Free (946-7000)