Character undergoes major dramatic journey in ‘Foxfire’

It's easy to think during the first few moments that this production of "Foxfire" is in deep trouble.

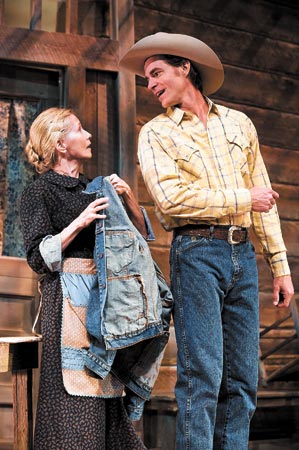

At the outset, we meet Annie Nations, a 79-year-old Appalachian woman, and Joyce Cohen, the actress playing her, comes across as way too young. In her dowdy dress, gray hair, and pulled-down stockings, she looks like something out of "The Beverly Hillbillies."

Amazingly, though, it doesn't take long for Cohen to win us over.

This 1982 play with songs by Hume Cronyn and Susan Cooper deals with a complicated issue: What's more important, place or people? Annie's lived in her impoverished home in the Blue Ridge Mountains of Georgia ever since she was an adult. The only company she gets on a regular basis is the ghost of her late husband, Hector (Will Zahrn). Son Dillard (John Bisom), a country singer, urges her to leave the past behind and join his family in Florida. Dillard, though, is having his own troubles. He can't seem to connect the present to what's come before. The script chides modern America for losing some core values, but makes clear that some of those "values" deserve to be lost.

Director Kathleen F. Conlin and scene designer Bill Forrester have taken great care in making sure that the physical atmosphere is the sort of place we'd want to call home. We understand Annie's reluctance to leave.

But the engine of this production is, as it should be, the actors. Cohen's character undergoes a major dramatic journey, and the actress is a master at communicating it. Cohen's face allows us to "see" every contradictory thought in Annie's head.

Zahrn's Hector represents yesterday, and Zahrn presents both a loving and frightening picture of what yesterday was like. Zahrn comes across as a hardworking, practical man who loves his family, but is dictatorial and tunnel-visioned. The actor dominates his scenes the way Hector dominates those around him.

Bisom's a genial performer, and we have no trouble believing his character is a country singer. His concert scene is as thrilling to us as it's supposed to be to the audience in the play.

The script is a tad too weepy at times, and while Conlin often rises above it, she sometimes succumbs. I occasionally felt my tear ducts being unfairly manipulated.

But the show earns much of its emotional pull. It instigates self-examination with a gentle, folksy prod.

Anthony Del Valle can be reached at DelValle@aol.com. You can write him c/o Las Vegas Review-Journal, P.O. Box 70, Las Vegas, NV 89125.

Utah Shakespearean Festival

2 and 8 p.m. (MDT) Mondays-Saturdays (through Aug. 29)

Adams Shakespearean Theatre and Randall L. Jones Theatre, Cedar City, Utah

$23-$66 (800-752-9849; www.bard.org)

"Foxfire" Grade: B+