Artistic director opens up about his hopes for Nevada Ballet Theatre

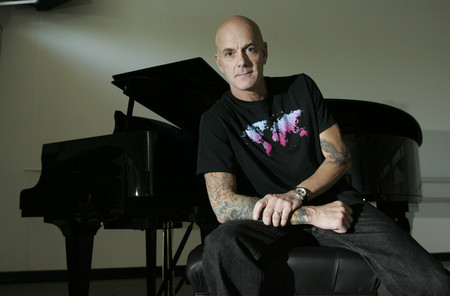

Tats down the arm. Shaved head like a bullet. Biker chic. Ballet.

That's not one of those "which-of-these-doesn't-belong" high school quizzes.

They all belong. They're all James Canfield.

"I am an individual of great integrity and it's not because I read about it, it's because I've lived it -- I've been dancing since I was 5, I left home at 13 and it's a hard-knock life," says Canfield, on the verge of his first full season as artistic director of Nevada Ballet Theatre after playing caretaker as interim chief. And if he's a taskmaster, that's because he's determined that his dancers will master this task.

"I want to be a force to train a child and I have to back off at times. A lot of times it's looked upon like it's an inappropriate style of education, and it's not. It's the real world. If your child and you are going to put that much time and effort into it, then I want you to be ready."

Passionate, tenacious, tough, creative, not unfamiliar with controversy -- Canfield fills all the bills. "Anybody who knows me is not afraid of me, they know what I ask of them is nothing more than I ask of myself," he says. "I ask them to come in and not take for granted that they're going to walk through that door tomorrow because anything can happen, so what are they saving it for?"

He's also an affable gentleman, speaking earnestly at the troupe's headquarters in the northwest valley about a company that, despite budget shrinkage and consolidation of his crew of dancers, triggers genuine zeal in this ballet lifer, first stirred after witnessing one of the group's collaborations with Cirque du Soleil's performers. "When I saw that, I thought, 'What depth in this company, what talent there is in this room.' It excited me and that's what really drew me to wanting to become the director."

Founding artistic director of the Oregon Ballet Theatre in Portland and a former Joffrey Ballet dancer, Canfield took temporary control of Nevada Ballet Theatre and its affiliated academy in March 2007, after the departure of Bruce Steivel -- during which time he brought the company to perform at the Kennedy Center -- and was made permanent pooh-bah last January, with an eye toward prepping the troupe for its future as an anchor tenant of the new Smith Center for the Performing Arts in 2011.

A reputation as a progressive artist and provocateur came with him.

"There was a line I heard from somewhere that said, 'He attracts controversy like lint,' " company executive director Beth Barbre told the Review-Journal when Canfield was appointed.

Tsk-tsking stemmed from pre-Nevada Ballet Theatre choreography perceived in some quarters as excessively sexual. "It's just one or two pieces," Canfield says. "Just for the record, because this has come up a lot of times, the clothing of a dancer is skintight. ... It's already sexual, they don't have to touch, just stand there in their costumes. It's perception and what people have or have not been exposed to. All of my work does not contain that. To get that perception, people are reading my past, and that's 20 years of time."

Instituting performances at public venues -- restaurants, hotel lobbies, etc. -- and talk-back sessions with artists are among community outreach programs contributing to what Canfield calls a holistic approach to Nevada Ballet Theatre management. "It starts in our academy, classical ballet training," he says. "We're plucking kids out of the community, they get the training and we launch their career here or anywhere in the world. But there hasn't been enough of a bloodline, if you will, through the academy and how our education and outreach programs feed into the academy."

Canfield has assembled a season lineup encompassing both adventurous and established works that stretch from a new version of the holiday chestnut "The Nutcracker" and the legendary George Balanchine's "Rubies" to his own pieces: "Coco," inspired by the life of fashion designer Gabrielle "Coco" Chanel and set to Edith Piaf tunes, as well as "Jungle," an evocation of both the natural and urban variety. Last season, Canfield staged his ballet "Up," set to seven versions of the pop standard "Blue Moon," and "Neon Glass Pas de Deux," an exotic blend of ingredients suggested by the creations of glass sculptor Dale Chihuly and the avant-garde music of Philip Glass.

"The traditional NBT audience is worried that the more classical pieces are no longer going to be found at NBT," Kelly Roth, head of the dance program at the College of Southern Nevada, told the Review-Journal just before mounting his annual "Dance in the Desert" program recently. "(Canfield) wants a new audience for NBT, but it's dangerous to alienate your base. The younger, hipper audience he envisions probably doesn't have the same financial resources the older fans have."

Canfield dissents, noting that his repertoires have always integrated diverse styles, and that some critics single out certain pieces for a label they can hang on him that disregards the range of his work. "Not everyone in this global environment has the same taste," he says. "When you're reaching out, someone's not going to be happy. I'm not trying to intentionally say thank you to anyone or get rid of anyone, but the world is that large and we're all here." The long-term vision, he adds, is to dovetail different dance fans into one fan base. "We're trying to attract new audiences, retain old audiences -- in the sense of past audiences, not old in age -- and build a repertoire that will be for both audiences so when we move into a 2,200-seat theater, we're all together."

Ballet lovers bonding, symbolically linked arm in arm, connected by the one covered in tats.

Contact reporter Steve Bornfeld at sbornfeld@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0256.