3 reasons The Who may be the greatest rock band of all time

The dude decked out like a paisley buccaneer casts an annoying glance at Tommy Smothers, because who wouldn’t?

Roger Daltrey may be feigning irritation at one of the hosts of the show he’s about to set ablaze, but that’s the only thing he feigns over the course of the next three highly flammable minutes.

It’s Sept. 15, 1967, and The Who are making their first, and only, U.S. variety show appearance on “The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour.”

“This song really goes!” Tommy Smothers gushes prior to the band knifing into “My Generation.” “You’re gonna be surprised by what happens because this is excitement.”

Daltrey glares into the camera hard as the song begins, the band mostly stoic at first save for drummer Keith Moon, who pistons up and down behind his kit, flailing about like a human whirligig caught in a stiff wind.

The song, the band, the mood — everything is confrontational, in your face and terribly exciting.

The tune ends with a bang — literally. Moon had packed his bass drum with explosives, detonating them at the conclusion of their performance, leaving guitarist Pete Townshend temporarily deaf.

Undeterred, the guitarist stabs his instrument into his amp before wielding it like a mallet in one of those strongman games found at county fairs and smashing it into the stage.

It’s one of the most incendiary TV moments in rock and roll history, an early testament to the power of one of rock’s most powerful acts.

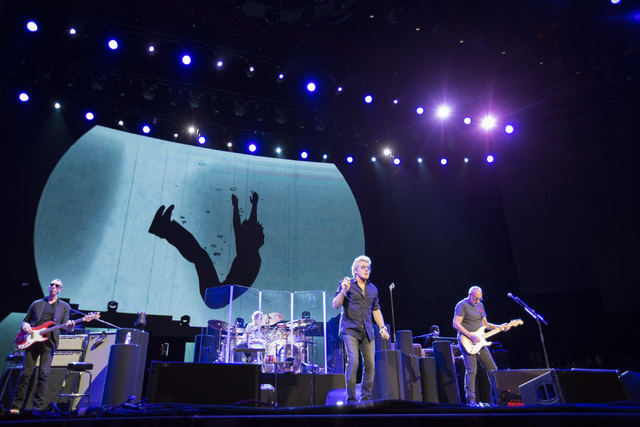

Fifty years later, The Who are still bringing it, about to kick off a six-show stint at the Colosseum at Caesars Palace.

Are they the greatest rock and roll band ever?

Well, that’s highly debatable, but here are three arguments in their favor:

They popularized the rock opera

OK, so this one is kind of like the advent of Jagermeister, something totally awesome in the hands of pros, but which can just as easily lead to the emptying of one’s stomach contents when left to lesser practitioners.

Now, The Who didn’t invent the rock opera — music nerds tend to argue between the British band Nirvana’s “The Story of Simon Simopath” and The Pretty Things’ “S.F. Sorrow” as the first example of this kind of elaborate song suite — but they certainly popularized it, first with 1969’s “Tommy,” then with 1973’s “Quadrophenia.”

Both those albums toe the line between artistic ambition and excess, a balancing act akin to walking a tightrope while hoisting an anvil above your head.

But think about where this band came from, musically speaking: Just four years before the release of “Tommy,” they debuted with “My Generation,” an album full of curled lips and fat-free proto-punk jams. That they would develop so much in a relatively short period of time at least partially compensates for being the group that paved the way for Savatage’s “Streets.” (Check it out if you want to save money on ipecac.)

They’re responsible for the Marshall stack

What’s a more iconic visual representation of the toe-curling, gut-roiling, eardrum-hammering power of rock and roll than the Marshall stack?

Go ahead, close your eyes and imagine a Judas Priest or a Slayer gig without that trademark, Stonehenge-sized backline. Now open them again safe in the knowledge that this nightmare scenario will never come to fruition.

And it all began with these dudes.

In the early ’60s, Townshend and Entwistle engaged in an arms race of sorts to see who could generate as much volume as possible — part of this was simply to be heard over Moon’s thunderclap-loud drumming. They were friendly with Jim Marshall, the West Londoner who founded Marshall Amplification, and at their urging, he created the four-valve power amp.

It was Townshend who first started stacking his amps atop one another, for reasons both practical (there was only so much space on the stages they were playing back then) and performance-related.

Speaking of which …

They turned feedback into an art form

One of the main reasons that Townshend started stacking his amps was that by elevating them closer to his guitar, he could induce feedback from its pickups.

Oh, what a glorious, dissonant din he conjured, one that would inform the music of legions of shoegaze, noise rock, punk and metal bands in the ensuing decades, from Sonic Youth to My Bloody Valentine, Velvet Underground to Big Black.

“I started to use it, I started to control it,” Townshend explained of his initial experiments with feedback in the band’s seminal biography, “Before I Get Old: The Story of The Who.” “I regulated the guitar so that the middle pickup was preamped on the inside with a battery and raised right onto the strings so that it would feed back as soon as I switched it on. And I could control it and go through all kinds of things.”

It wasn’t just noise for the sake of noise; it gave his playing its own unique voice — or shriek, rather — simultaneously heightening its intensity and broadening the vocabulary of his instrument.

It was a major innovation for so many strains of music — and the manufacturers of protective earwear.

Contact Jason Bracelin at jbracelin@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0476. Follow @JasonBracelin on Twitter.