Why this family of British aristocrats still obsesses the public

What is it about the Mitfords? Even today, the sisters — born to minor British nobility, deprived of formal education, raised to marry well — have a surprisingly strong grip on transatlantic culture.

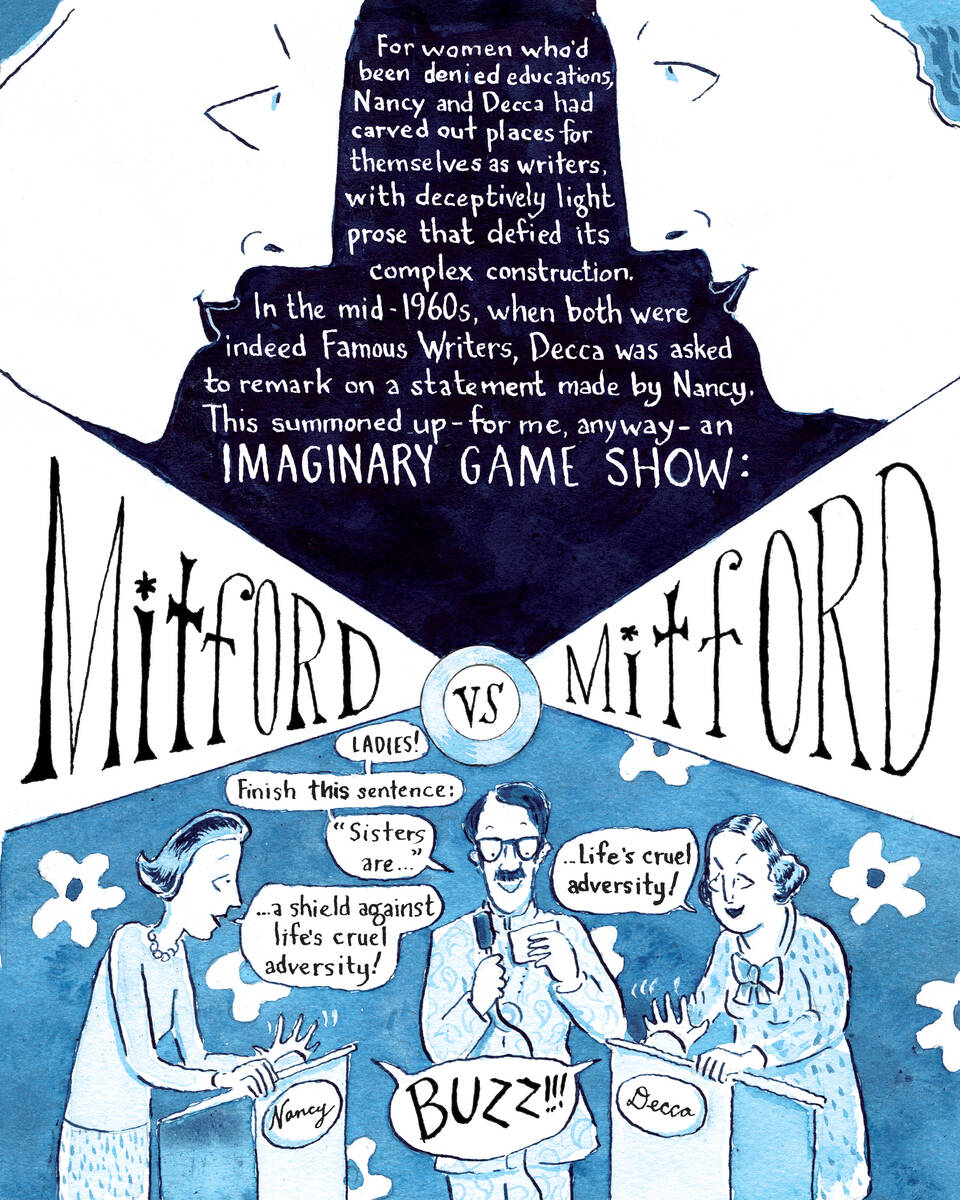

“They were originally celebrities simply because they were aristocrats, who were like the reality show stars of today,” said cartoonist Mimi Pond, whose graphic biography of the family was published in September. In the course of their various creative, political and romantic escapades, they rubbed elbows with the Black Panthers and the Kennedys, Charles de Gaulle and Evelyn Waugh: “Through their actions, they just defined everything about the 20th century.”

“Mitford mania” — as one of the sisters put it — comes in waves. We’re riding one now. (The last one, only a few years ago, inspired a series of cozy mysteries and a sweater by Gucci, products that landed atop a heap of existing biographies, movies and — so far — one musical.)

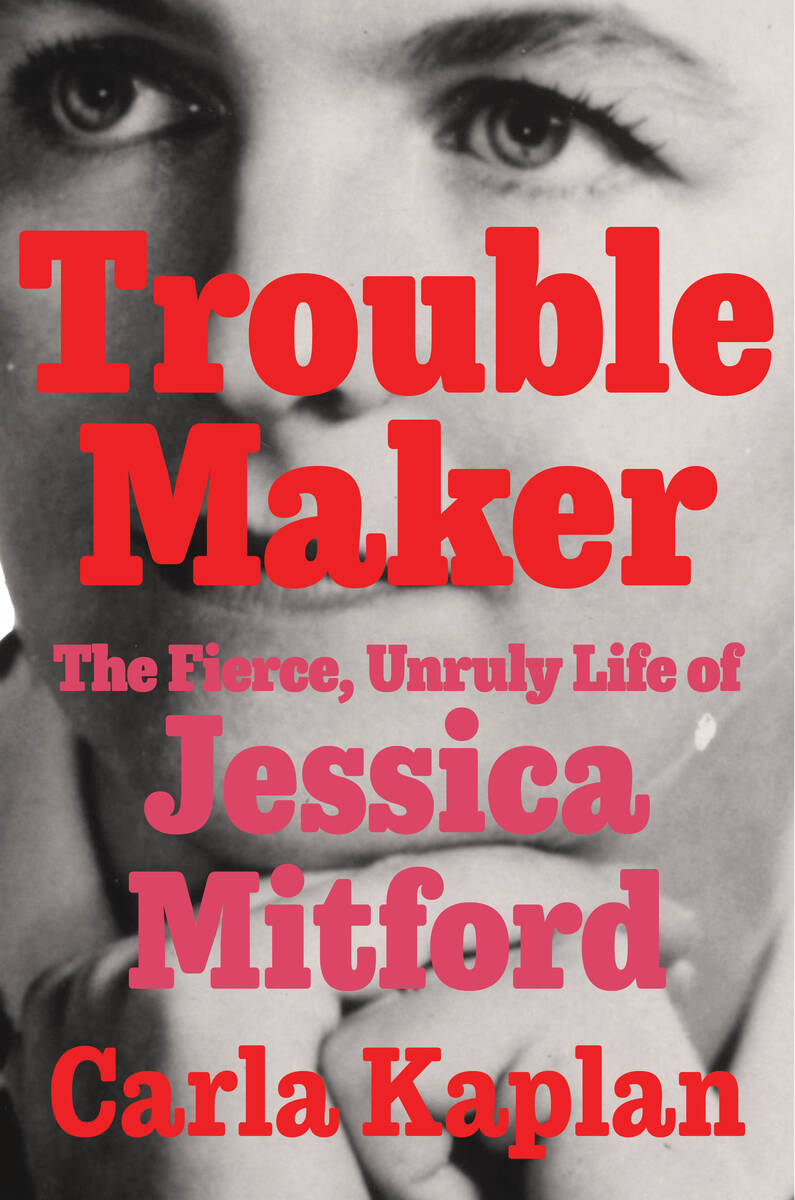

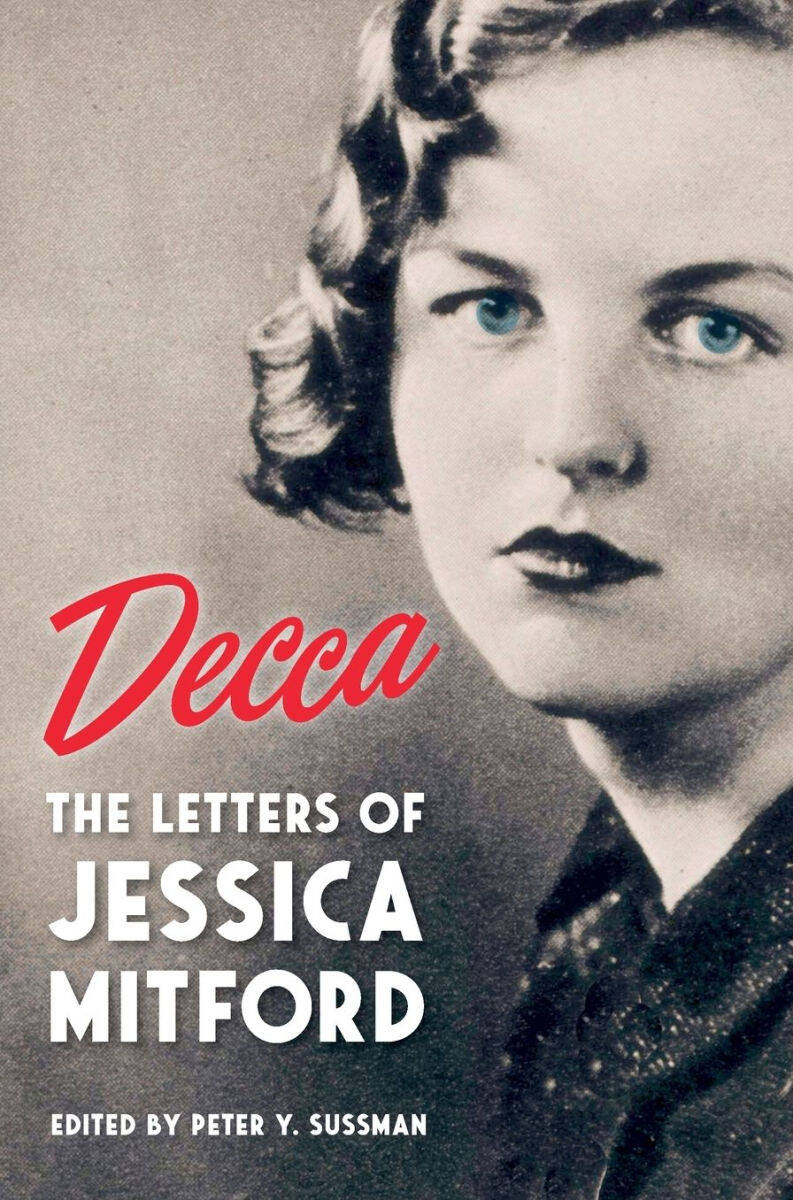

This year has yielded a bumper crop of Mitfordiana: Along with Pond’s book, “Do Admit!: The Mitford Sisters and Me,” there’s “Troublemaker,” Carla Kaplan’s biography of Jessica “Decca” Mitford, which characterizes her as the sister who broke the Mitford mold with her leftist commitments and draws on a fresh trove of archival materials; a collection of Decca’s letters, edited by Peter Y. Sussman, was reissued this year. A frothy BritBox series called “Outrageous” aired this summer, and “The Party Girls,” a new play by Amy Rosenthal, toured Britain through the fall.

“You have this group of six women who are extraordinarily creative and brilliant. They were Energizer bunnies, every one of them, and so smart — and they had no outlet,” said Kaplan, a professor of American literature at Northeastern University. “Their creativity, for the most part, explodes in really unfortunate ways.”

‘They fed those stories’

Here’s just a slice of it: Nancy, one of London’s “bright young things” in the 1920s, became a bestselling author; her novels “The Pursuit of Love” and “Love in a Cold Climate” remain especially popular today. Diana married Oswald Mosley, founder of the British Union of Fascists. Unity was infatuated with Hitler and shot herself in the head when Britain declared war on Germany; she survived, with permanent brain damage. Jessica moved to the United States, where she devoted herself to muckraking and social justice causes (and became a card-carrying communist). Deborah had an entrepreneurial knack that Martha Stewart would envy, rebuilding her husband’s ancestral seat, Chatsworth, and opening it to the public. Only one, Pamela, led a relatively low-profile country life.

“Part of the funny paradox of the family and of all the sisters is they constantly proclaimed their disdain for the press, their disdain for popular culture, their disdain for stories about themselves — and they fed those stories at every moment,” Kaplan said.

What draws people into the fandom? The Mitfords scratch an escapist itch, with their isolated childhood and glamorous, imperious eccentricity. (Everyone has a favorite fun fact: Unity wore her pet snake, Enid, around her neck as a ballroom accessory! Diana slept under a fur coat while in prison! Pamela smuggled the fertilized eggs of a crested Swedish chicken in a box of chocolates!) The sisters also feel appealingly literary — not just in their florid antics but in how they expressed themselves: glibly and colorfully.

A family divided

“If you like other worlds, they’re almost as much of another world as Harry Potter is of another world,” Kaplan said. Long after the sisters’ deaths, you can still find people declaring themselves partisans of one Mitford or another, taking sides about whose version of events — detailed in letters, memoirs, interviews and more — they believe.

Pond writes in her book, “As an American, I knew royalty was kind of dumb, but my life lacked pageantry.” The Mitfords supplied plenty.

Today, “people have finally figured out that it’s a moneymaker,” said Pond, who said she vowed to herself, “If anyone’s going to do Mitford merch, it’s going to be me!” (So far, she has made coasters, tea towels and a set of pins featuring the sisters’ faces; only Jessica and Nancy have sold in significant quantities.)

Rosenthal, though, said that for years she had difficulty getting people to even read the script for her play. “I think people who don’t know much about them have got a lot of assumptions: Either they’re a cackling clan of posh girls who were comic in the extreme, and irritating — or there’s the version where they’re just all a load of Nazis.”

But as the cast and crew brought the show to audiences across Britain, the Mitfords’ political polarization — including some members’ fascist sympathies and antisemitism — felt more painfully relevant. “Everything about the world we live in has come to hold the chalice of the play more firmly than it did when I wrote it,” Rosenthal said.

“Almost everybody who has any kind of family these days is experiencing the stress and the pain of being in a divided family politically,” Kaplan said, “of having family members who are unaccountably political enemies and who you can’t help loving, but you can’t make any sense of.” The Mitford saga, she said, “gives us an incredible vision of that.”

This is an excerpt from a Washington Post story.