James Gandolfini was so much more than Tony Soprano

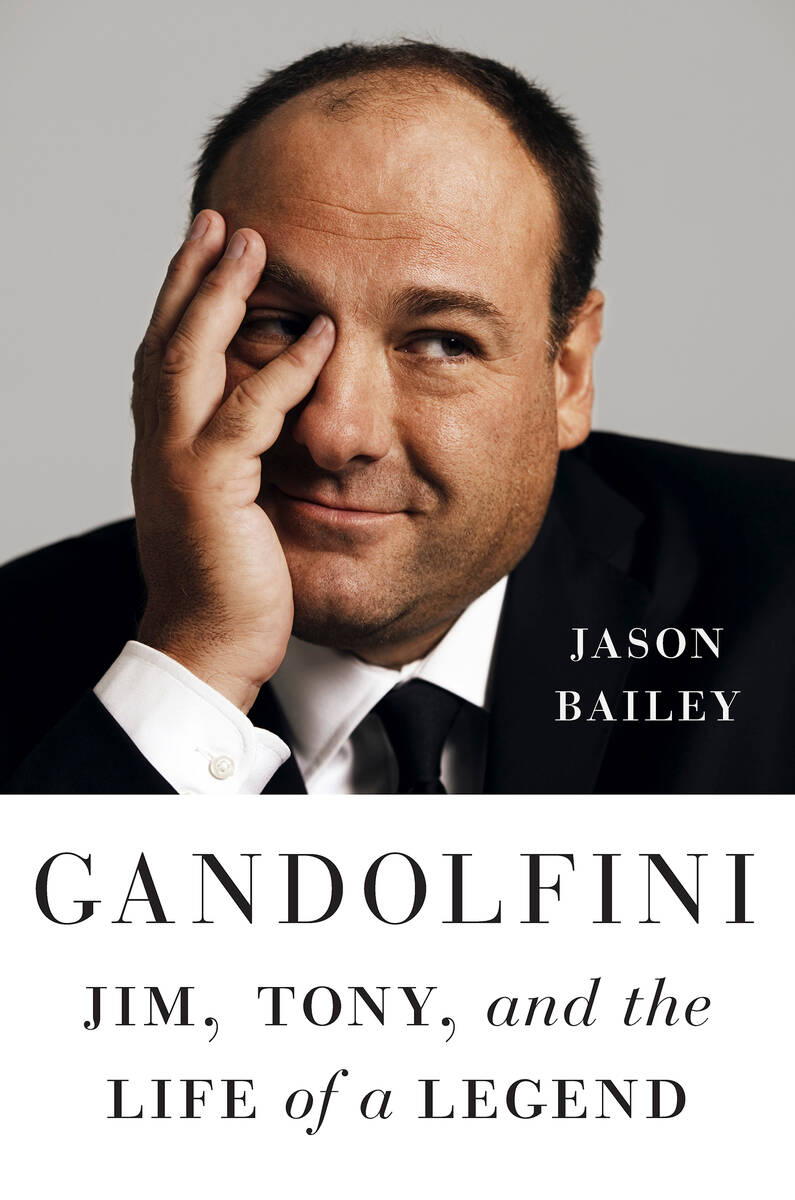

At first glance it’s an anonymous, nearly self-canceling face: youngish/oldish, slack and pinched, enlarged and also shrunken by its receding hairline. It’s the face of your local barber or the guy who taught you world geography or the salesman who sold your dad his first Nissan. It takes another glance or two to draw a bead on the eyes, which initially present as wells of melancholy until they’re sparked into merriment or seduction or bemusement or an ice-cold rage that stops your breath because it was the last thing you were expecting.

In the end, there was nothing anonymous about James Gandolfini, though he might have wished there were. He followed in the trail of Paul Muni, Edward G. Robinson and Humphrey Bogart: character actors who were vaulted, against anyone’s expectations, into stardom. That each of them traveled the path of the desperado is no accident: Our culture likes the guys who rough us up a little, and if they don’t look like someone we’d bring home to meet our parents, so much the better because, in our theaters and living rooms, we can go back to their sketchy apartments and still hold them at arm’s length.

But what if the cost of that transaction is paid by the tough guy himself? That is the primary theme of “Gandolfini,” film critic and historian Jason Bailey’s judicious and deeply reported biography, which seeks to reclaim the actor from his greatest role.

Depending on where or when you met Gandolfini, he was James, Jamie, Jimmy, even Bucky. Our biographer settles on Jim, a name to encompass both the Jersey boy who excelled at basketball at Park Ridge High School and the driven young actor who came at New York with all the charm, force and talent he had in him. Success wasn’t too long in arriving: a supporting role in the 1992 Broadway revival of “A Streetcar Named Desire,” followed by a breakout film moment in Tony Scott’s “True Romance,” where his softly smiling hit man methodically terrorizes Patricia Arquette. Even then, he worried about being typecast. “If you ever have me play a gangster again,” he told his manager, “I will f---ing kill you.”

True to his principles, he turned down the second lead in HBO’s “Gotti” biopic. He didn’t want to do TV, either, but the next HBO offer was the one he couldn’t refuse: a starring role as a besieged North Jersey crime boss, stealing visits to a shrink while he shores up his teetering empire, family and psyche. It’s a premise that, as the simultaneously released “Analyze This” proved, could easily tilt into comedy. But creator and showrunner David Chase had something else in mind: the day-to-day attrition of a man’s soul.

The wonder is how many of us showed up for that dire spectacle. By the middle of its first season, “The Sopranos” was cable’s highest-ranked program, clocking 10 million viewers per episode, and over the course of its eight-year run, the numbers kept climbing. We didn’t know it at the time, but the medium of television had been, in the show’s vernacular, whacked. The antihero was now the hero, and Tony Soprano, in Gandolfini’s indelible rendering, came to preside over not just a stack of corpses but a long and still-advancing line of hollow men.

So if you love your Dexter, your Don Draper, your Walter White, say a little prayer of thanks for their godfather. Throw in a prayer, while you’re at it, for Gandolfini, who, by general agreement, was not the guy he played.

Bailey has interviewed hordes of his intimates and colleagues and come away with a unified field theory: Our Jim was a “sweetie-pie,” “a soft-spoken, kindhearted, genuinely modest average Joe,” “a big, lovable, insanely talented man.”

This is an excerpt from a Washington Post story.