A treasure trove of new books to read during Pride Month

The dazzling variety of current and upcoming books on LGBTQ themes is a reassuring reminder of how far we’ve come.

This year, fans of queer romance can read books set in the worlds of Formula 1 (“Crash Test”), clandestine Victorian clubs (“To Sketch a Scandal”) and Italian restaurants (“Pasta Girls”). In July, Phaidon is publishing a lavish survey of global queer art as a companion piece to Jonathan D. Katz’s Chicago exhibition “The First Homosexuals,” while the queer Korean vampire murder mystery “The Midnight Shift,” by Cheon Seon-Ran, will draw first blood in August.

These books are variously warm, comic, sad, jubilant, curious, violent and erotic. Each has insights of its own to offer, but they’re united by their awareness of the continuing vulnerability of lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans and queer people.

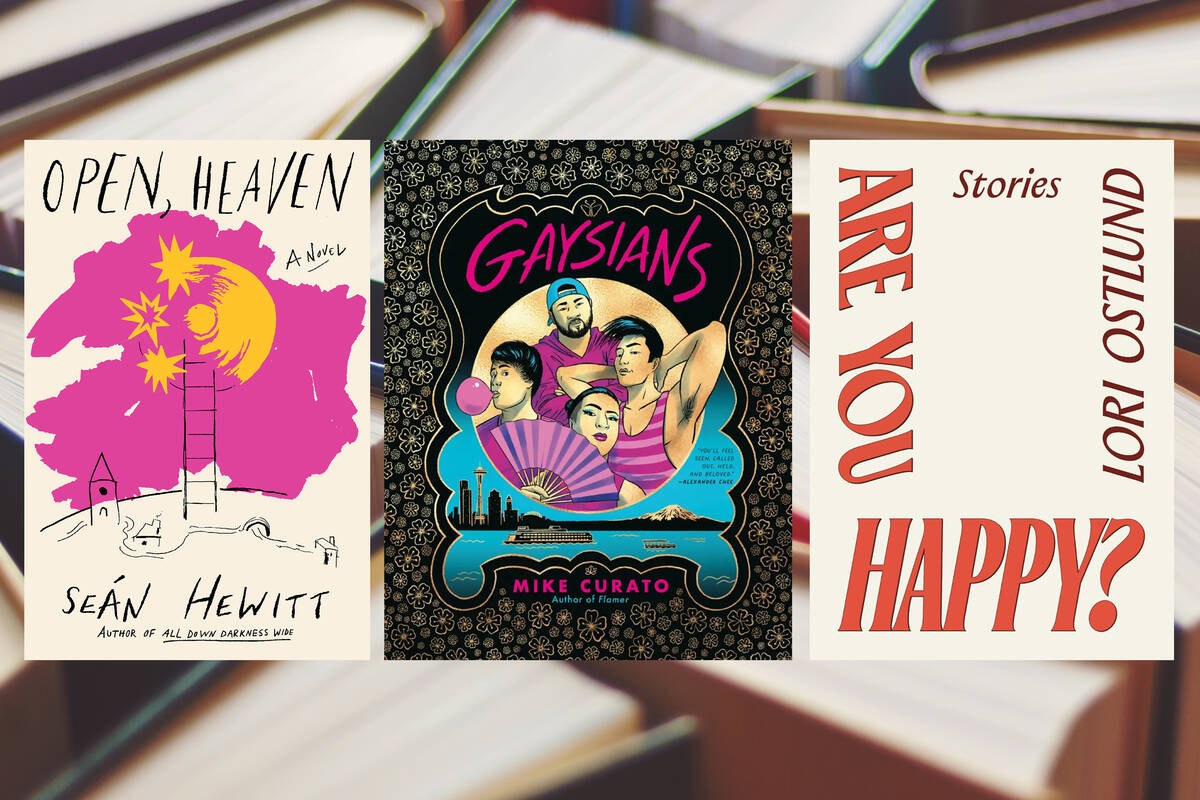

“Gaysians,” which is “Flamer” author Mike Curato’s first graphic novel for adults, doesn’t shy away from violence, racism and transphobia, outside the community or within it. The story, about a group of young Asian Americans living in Seattle in 2003, is most powerful when Curato unleashes his more expressionistic side to capture different characters’ traumatic flashbacks and glimpses of historical tragedy. But this darkness is offset by the story’s cozy, reassuring focus on friendship and found family.

One of the most curious books of the season comes from “the emerging field of queer ecology.” In “Forest Euphoria: The Abounding Queerness of Nature,” Patricia Ononiwu Kaishian makes a powerful case for trying to understand nature without the artificial binaries and hierarchies of human societies. Though she is, by training, a mycologist — a fungi specialist — she embraces all life forms, a disposition derived from her understanding of diversity being nature’s “very premise.”

I certainly know more about snail sexuality than I did before I opened it.

One of the summer’s most hotly anticipated titles is “Deep House: The Gayest Love Story Ever Told.” Jeremy Atherton Lin’s follow-up to “Gay Bar,” for which he won a National Book Critics Circle Award, is a strong cocktail of memoir, legal history and sociology. He proceeds along parallel tracks to tell the romantic story of his relationship with a British man he met in 1996 and the jagged path taken by American and British legislatures and courts to eventually grant basic rights to people in same-sex relationships. “We were aliens in each other’s countries,” he writes, “because in our own we remained second-class citizens.”

Reading Lori Ostlund’s excellent new short-story collection, “Are You Happy?,” I found myself reflecting indignantly on the subtitle Lin chose for “Deep House.” Surely laying claim to being the gayest love story ever told — or the gayest anything, however flippantly — risks devaluing that which isn’t quite so … overt? Promiscuous? Coastal? Male? Though Ostlund’s stories dwell less on heady sex and front-line politics, other hallmarks of the LGBTQ experience are everywhere present. Her protagonists have parents who never accepted them and colleagues they never told about their significant others. Ostlund’s stories may be less graphic than Lin’s memoir, but there’s nothing less gay about them. Besides, the lesbian couple that runs a furniture store named after Jane Bowles’s “Two Serious Ladies” could hardly be gayer — that’s a pretty sapphic bit of branding.

Also set a little further from the madding crowd is Seán Hewitt’s first novel, “Open, Heaven,” which takes place largely in a “foggy northern village” in England. It’s all a bit reminiscent of the film “God’s Own Country” — in rural Thornmere, to be gay is to be lonely and furtive — though with more longing and less flesh. When James, our sensitive, stammering hero, comes out in 2002, Britain is still a year away from repealing Section 28, a sliver of legislation that effectively quashed discussion of sexuality in England’s schools, and he is left feeling like a stranger in the only home he’s ever known. While delivering milk bottles one morning before school, he meets Luke, a boy lodging with his aunt and uncle while his dad is in prison. Before long the strong-jawed Luke is all James can think about — but does Luke feel the same way?

The book’s appeal may depend on its readers’ willingness to take adolescent romantic longing as seriously as we do when we’re young. It succeeds because Hewitt knows when to stop — he casts a spell, like first love, that he knows can’t last forever. Or can it?

This is an excerpt from a Washington Post story.