Exhibit looks at comic book censorship

Looking back over the past several decades, it’s amazing how often collections of words and pictures have rubbed so many people the wrong way.

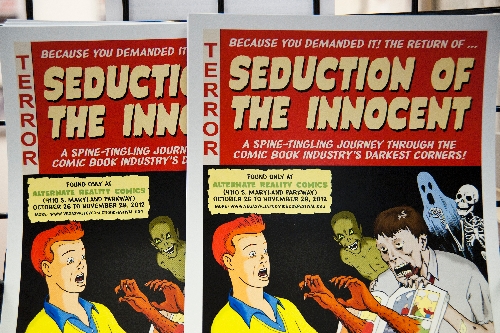

And just what happened when those collections of words and pictures – you know them as comic books – angered the powers that be can be seen in “Seduction of the Innocent,” an exhibition that runs through Nov. 28 at Alternate Reality Comics, 4110 S. Maryland Parkway.

The exhibition is part of the Vegas Valley Comic Book Festival, which is, in turn, part of the Vegas Valley Book Festival. Curated by Las Vegas writer/illustrator Pj Perez, the exhibition features reproductions of rare comic book covers, photos and artwork.

That comics would even be thought of as worthy of censoring might surprise readers who aren’t followers of the art form. When a previous iteration of the exhibition was mounted a year ago at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas’ Marjorie Barrick Museum, some viewers “were sort of ignorant of” the 80-year history of comic books in America, Perez said.

Last year’s showing “served its purpose so well, we decided to bring it back so more people would be exposed to this,” he said.

Perez describes the exhibition as a “visual timeline” of key events in the history of comic book censorship since the 1930s. It was then, according to Perez, that comic strips created for newspaper syndication began to be collected into the first true comic books.

Back then, criticism and censorship of comic books were likely to revolve around issues such as vulgar street language, disrespect for authority and stereotypical depictions of ethnic cultures, he said.

By the ’40s, the now wildly successful entertainment medium started to become the focus of a backlash that would see comic books blamed for such social problems as juvenile delinquency.

“Obviously, we spend a good amount of time on the mid-’50s,” Perez said. “The inspiration for the show’s title is, of course, the Fredric Wertham book ‘Seduction of the Innocent.’ “

Wertham, a New York psychiatrist, asserted the existence of a link between juvenile crime and depictions of violence, drug use and sexual imagery in comic books. When “Seduction of the Innocent” was published in 1954, it created a public uproar and led to congressional hearings.

Wertham “is amazing, because so many points he brought up were so over-the-top,” Perez said. “One thing I find really interesting is that comics basically were a scapegoat, and a really easy scapegoat.”

Faced with the threat of government regulation of comics, publishers even created the Comics Code Authority, a self-regulatory censorship mechanism that for years covered every comic book sold at newsstands, Perez said.

The exhibition covers the evolution of the comics industry in the wake of Wertham, from the underground comics of the ’60s to the rise of independent comic stores in the ’80s to the legal battles comic book retailers and creators still fight.

Is there something about the medium that makes comics a target of censorship? It’s true, Perez said, that “because of the medium itself, a lot of writers and artists kind of felt like they could fly under the radar and get away with things you couldn’t pull off in more mainstream media.”

So, he said, creators sometimes would push the boundaries of, for example, depicting violence and sexual imagery. Also, Perez said, “you have a medium where I don’t think this sort of (adult) material was expected, so when parents discovered it, they were more shocked than you would have been with a dime store novel.”

Today, censorship battles continue in the form of comics and graphic novels landing on library blacklists, legal actions against comic retailers, and travelers being held for questioning and even arrested for possessing allegedly obscene comics, Perez said.

Ralph Mathieu, owner of Alternate Reality Comics, noted that there still are comic book retailers in, for example, the Southern United States who “have to be cautious about some of the books that are put up for display.”

“It’s not the big industry-targeted censorship that happened back in the day,” Perez said. “But there are little cases of things popping up – people being arrested for having stuff or selling it. Shops have been put out of business over legal fees because they carried a certain style of manga or graphic novel.”

And that, he said, is “straight-up trampling on First Amendment rights.”

Contact reporter John Przybys at jprzybys@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0280.