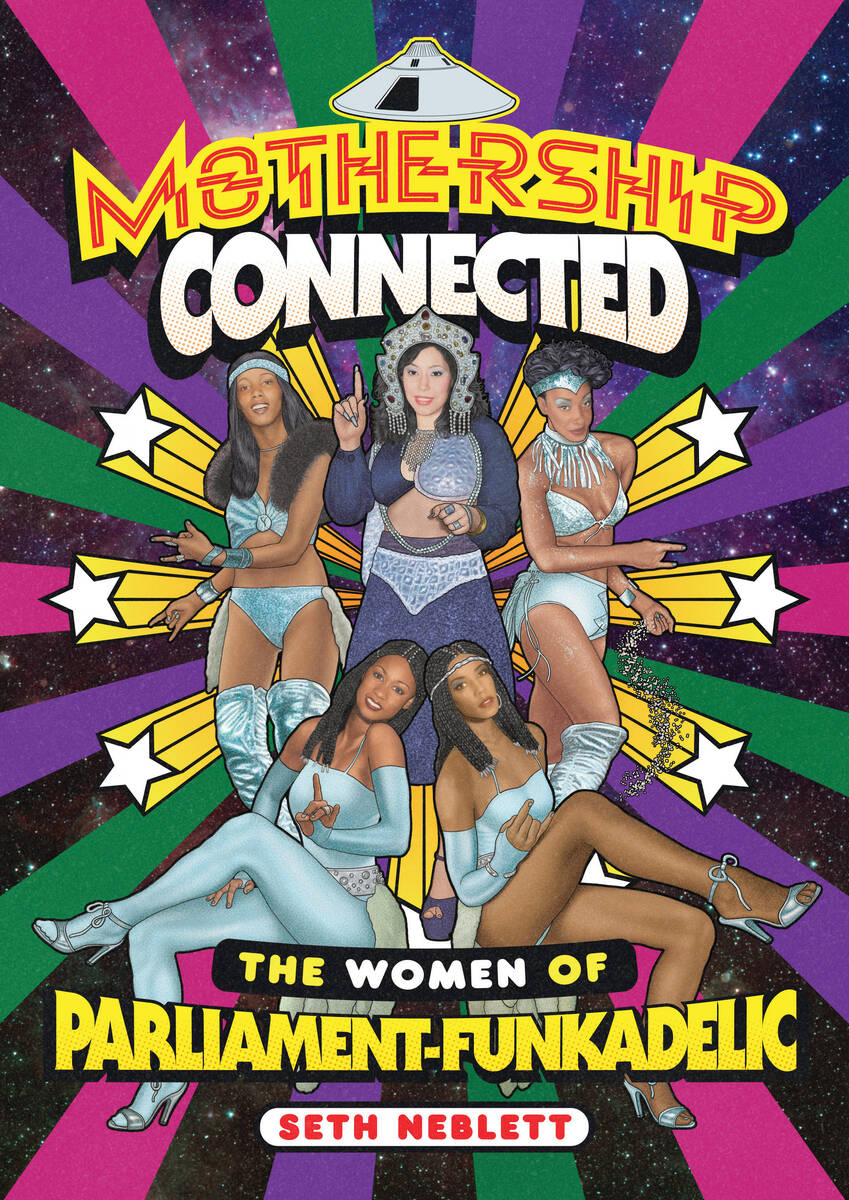

The women of Parliament-Funkadelic finally get their due

During one number at a Parliament-Funkadelic concert a few years ago, I watched as 15 or 20 band members and hangers-on partied and boogied and wandered around onstage, including an old woman with a hat and a purse who looked as though she had lost her way to the bus stop. A few minutes later, the stage had emptied of everyone except a lone band member, a plus-size man in a diaper playing a saxophone. It was a show, but it bordered on a religious experience.

As Seth Neblett puts it in his new book, “Mothership Connected,” P-Funk (as the band is called in shorthand) is in “many ways like a musical-spiritual cult.”

Neblett has an insider’s perspective on the band: His mother, Mallia Franklin, was one of its members. He begins with an anecdote about being in the dressing room with his mom and his P-Funk “aunties” before a show. As the women slipped into silver bikinis and thigh-high boots and arrayed themselves in “wild manes of hair and long, intricate braids that reminded me of strands of onyx licorice,” he writes, it was “like watching superheroines preparing for battle.”

Neblett’s book is the story of Franklin, Debbie Wright, Shirley Hayden, Dawn Silva and Lynn Mabry, five women who were key figures in the funk ensemble famous for some of the more outrageous stage performances in showbiz history.

A new sound

Singer, songwriter and producer George Clinton was (and still is) the center of P-Funk — its bandleader and its creative mastermind. He was cutting hair in a Plainfield, New Jersey, barbershop in 1956 when he formed a doo-wop quintet called the Parliaments (after the popular cigarette brand). Within a few years, they signed with soul powerhouse Motown Records, which promptly shelved the group, saying their style was too close to that of its biggest hitmakers, the Temptations.

A frustrated Clinton took his group to another label, changed its name to Funkadelic, and within a few years had not only hooked into the new psychedelic sound that was changing music the world over but inspired his musicians to trade in their sharkskin suits for thrift store outfits, tie-dyed clothes, dashikis and love beads. Adding the band’s original name to the new one, Clinton created Parliament-Funkadelic and led what was to become a collective of more than 50 musicians into a free-for-all style that borrowed from acid rock pioneers such as Jimi Hendrix and Frank Zappa as well as James Brown and other rhythm-and-blues stalwarts.

Trying to define music in words is like describing a spiral staircase to someone who’s never seen one. Until recently, I thought that funk meant something like bass-driven percussive dance music with minimum melody and maximum syncopation. But you can probably get a better idea of what funk is by watching your Aunt Minnie take the dance floor at a wedding reception when the DJ cues up P-Funk’s “Night of the Thumpasorus Peoples.”

When Clinton brought the five women Neblett focuses on into the band in the ’70s, he divided them into two groups: the Brides of Funkenstein, who were meant to be more mainstream, and Parlet, which was funkier. In the words of Garry Shider, the band’s musical director, “The Brides seduced you into giving up the funk; Parlet was going to gonna make you give it up.”

‘Stories of survival’

Women may have been central to the success of P-Funk, but little has been written about them. Neblett wants their voices to be heard, so that these women can “reveal their stories of survival, how they got there and made it through, what it took to be a woman out front in the music industry at a time when misogyny was the expectation.”

Women in pop music, as everywhere else, have to navigate the bumpy road of gender expectations. While a male musician can typically inhabit a single, straightforward identity — heartthrob, intellectual, charming rogue — a woman is often expected to embody multiple, contradictory roles. She has to be both the good girl and the wild one, feminine and tough, rebel and role model. A man gets to be himself; a woman’s got to be everything and make it look easy and make sure everybody’s happy while she does it.

Neblett sketches the lives of Wright, Hayden, Silva and Mabry as they toured and partied with the group and then experienced the gamut of post-P-Funk possibilities, from Wright’s mental health issues and departure from the music industry, to Hayden’s and Mabry’s appearances on TV and in movies and their work with other musicians. But Neblett’s focus is on his mother, Parlet’s frontwoman, who died in 2010.

Clinton called her “the best talent scout that the funk ever had.” Her best find was bass player and all-around genius Bootsy Collins, who profoundly changed P-Funk’s sound as well as its stage act and propelled the group into its most legendary phase. Yet when the band was inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 1997, Franklin and the other women were not included, nor were they acknowledged when the Grammys presented P-Funk with a lifetime achievement award in 2019.

This is an excerpt from a Washington Post story.