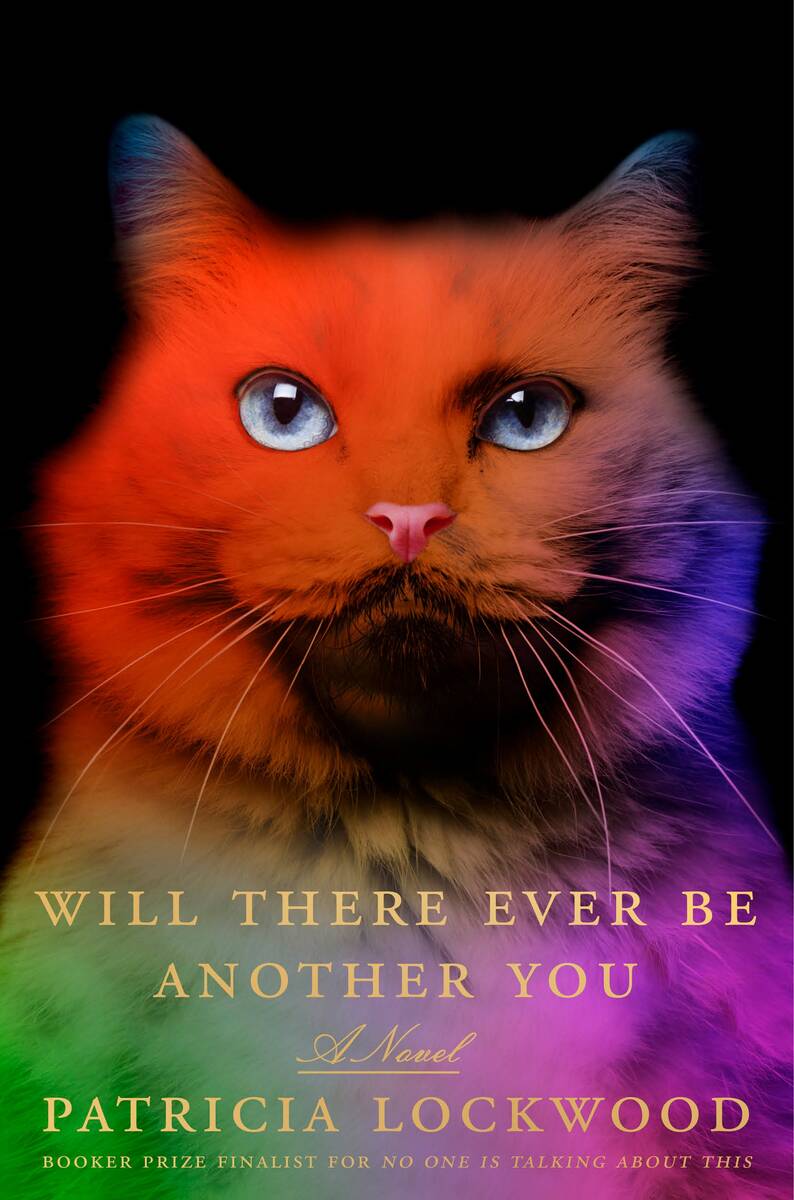

Patricia Lockwood’s new novel captures dizzying nature of illness

She wasn’t supposed to write about the pandemic; nobody was. It was too universal, too recent, to see clearly or render with much specificity. Besides, Patrica Lockwood writes in her second novel, “Will There Ever Be Another You,” the sweeping, most affecting events of her generation “had never properly entered into literature, because almost as soon as they happened they were transformed into propaganda.”

So Lockwood started writing about the early days of that era in private. In the resulting novel, the protagonist, a writer named Patricia, suffers from long COVID symptoms, which for her include existing “completely in the present” and gasping when she sees her own foot. She scrolls through forums and takes notes on the “broad, bronze” sky, “crisscrossed for once by nothing.”

Near the start of the novel, the narrator has a fever for 48 days; she adopts a new uniform involving an oversize “Looney Tunes” shirt; in her delirium, she becomes convinced that there’s “a secret number between two and three.” She isn’t herself; she is the unmoored chaos of the internet embodied. Or maybe she’s just a poet.

More so than an arc, the book takes the form of bright coruscations, shedding light on a few questions: Is a stable self a thing of the past? Does a consistent character depend on deep, lasting relationships? How might those flourish when we’re connected remotely?

The title — “Will There Ever Be Another You” — is taken from a Time magazine headline for a feature on Dolly, the cloned sheep. During the narrator’s months-long fever, she makes many of these lyrical references to reproducibility: a memory of Cabbage Patch Kid “cosmetic surgeries,” which swapped out injured limbs for new ones; a recollection of reading Walter Benjamin with her niece; and the tragic loss of a phone that held photos of another niece, who died of a rare condition.

The immaterial world is real because it’s affecting, Lockwood suggests. Then, something very material affects her narrator: Her husband winds up in a hospital after an emergency surgery gone wrong. Confronting his mortality, she thinks of the singularity of a Rothko painting: “in order to know how really beautiful it was, you had to be in the same room with it.”

Back at home, the narrator is in charge of redressing “the Wound.” Can a husband “just be open like that?” she wonders. At the same time, his delirious insights keep returning to her in poetic lines. On the brink of death, he told her he’d prayed to “Ganesh, Christian god, ancestors / Oh, I did Jah, too / World mother? Gaia / Also aliens.”

“Will There Ever Be Another You” is not a bisection of digital life and supposedly realer, more concrete events. Instead, it’s a portrait of a time when both sorts of experience, equally meaningful, shape us, melt us down and reshape us. In this world, it is possible, like the narrator’s father, to be “born again.” It is possible to try to give up writing for metalsmithing, to fail and return to writing, and to gift the fruit of that failure to a niece, for her to wear around her neck like a heavy amulet. It is possible that your long fever will break, and you’ll be able to leave your house, your fugue state. It is also true that you’ll get sick again, eventually.

Which isn’t to say, as a popular meme suggests, that “Nothing Ever Happens.” Toward the end of the novel, the narrator describes her husband’s scar, the wound she’d once tended, as “an event.” “Something happened here,” she writes.

This is an excerpt from a Washington Post story.