How ‘This Is Spinal Tap’ became an enduring rock-comedy classic

Abaffled rock band meanders the labyrinthian corridors of a Cleveland concert venue, searching in vain for the stage. A miniature model of Stonehenge is stomped into near oblivion by mincing dwarfs, as the lead singer looks on with astonishment. A drummer spontaneously combusts in a flash of light, leaving only a green globule on the seat behind his kit.

These are the images sewn into the living rock of our collective consciousness by “This Is Spinal Tap,” the story of a fake and vigorously ludicrous group that has proven far more beloved and influential than anyone would have expected following the film’s fraught initial release in 1984.

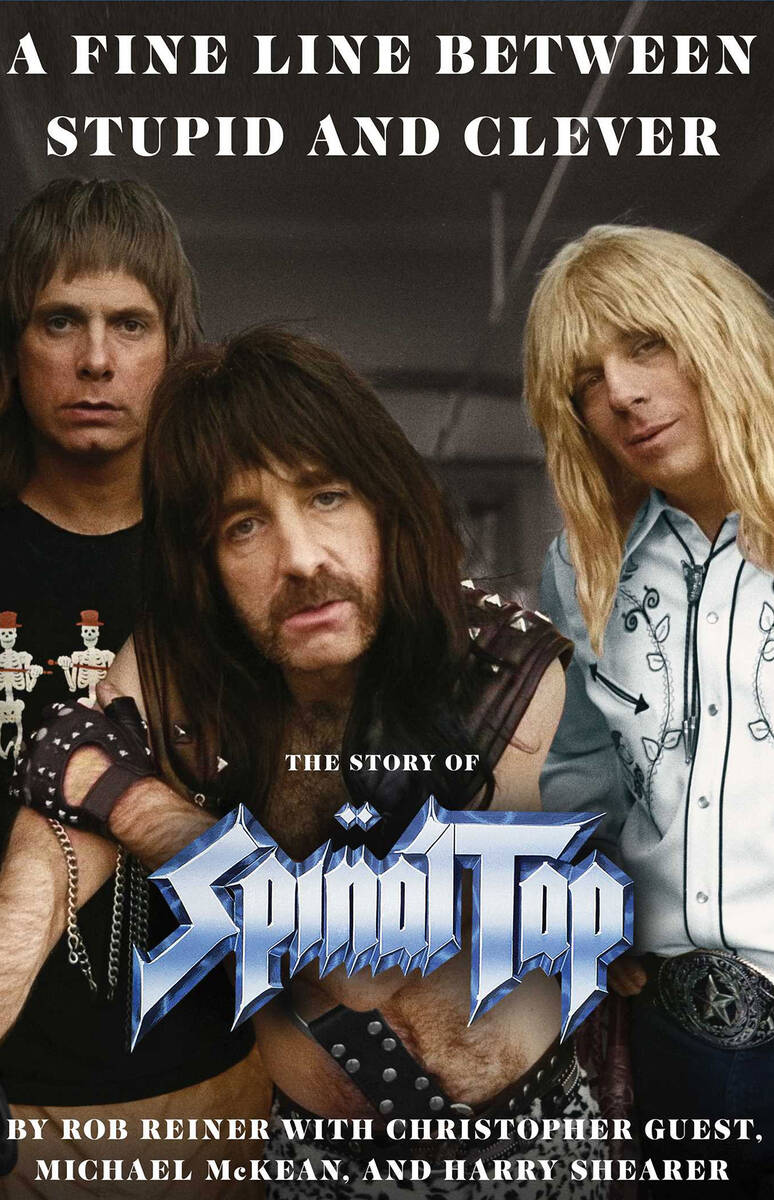

All of this and more — a lot more — is covered in “A Fine Line Between Stupid and Clever,” a new history of the band written by Rob Reiner and the actors who play Spinal Tap, with the help of culture journalist David Kamp. Turn the book over and you see the cover of a second volume, “Smell the Book,” about 60 additional pages of (fictional) oral history about one of England’s loudest bands.

These days, “This Is Spinal Tap” is generally regarded as one of the funniest and most enduring comedies ever made: a laugh-a-minute quote machine whose faux-verité style popularized the mockumentary form and served as a crucial influence on future classics, from “The Larry Sanders Show” to “The Office” to “What We Do in the Shadows.” What is revealed in “A Fine Line” is just how unlikely that legacy was for a scriptless film by Reiner, a first-time director working with a shoestring budget, no movie stars and a reluctant studio partner (the now defunct Embassy Pictures) that narrowly understood the concept, if it did at all.

Tap’s primary members were three of the great improv players in history: Michael McKean as the moony, New Age-adjacent singer-guitarist David St. Hubbins; Christopher Guest as the sweet-natured but remarkably thick lead guitarist Nigel Tufnel; and Harry Shearer as the walrus-mustachioed, pipe-smoking, self-styled philosopher-bassist Derek Smalls. All those actors went on to become treasured cultural totems. At the time, however, all were sufficiently obscure.

The film was an extended riff on the cinematic vernacular established by rock docs such as the Rolling Stones’ hybrid-concert film “Gimme Shelter” (1970) or The Who’s career overview “The Kids Are Alright” (1979), introducing the world of Tap through interviews, cutaways to old TV appearances and concert footage from their most recent, entirely calamitous American tour. Much of the movie’s appeal revolves around its close attention to the minutest details of the genre it satirizes.

It didn’t hurt that the music — written and performed by the deliriously talented McKean, Guest and Shearer, with some assistance from Reiner — is objectively perfect, skewering everything from inane hippie-era bromides to overwrought and ribald ’70s-style hard rock to the more asinine edges of Zeppelin-esque pseudo-spiritualism.

All of it taken together served as a kind of potted history of the rock era, as well as a withering critique of many peccadilloes of the baby boom generation: limitless vanity, an addiction to cultural relevance and an almost complete absence of self-awareness.

Now, when “This Is Spinal Tap” has been enshrined in the National Film Registry as “culturally, historically and aesthetically significant” and the phrase “these go to 11” has its own entry in the Oxford English Dictionary, all of this may have seemed inevitable. Reiner’s book makes abundantly clear that the far more likely outcome would have been for “This Is Spinal Tap” to sink without a trace.

An early rough cut of the movie ran to four hours, requiring a ruthless approach to editing that got it all the way down to 83 minutes. The executives at Embassy did not understand the picture at all and functionally refused to market it with any enthusiasm. Test screenings were catastrophic. All these decades later, Reiner still seems startled by the success of the movie and deeply attuned to its inherent ironies. This month saw the release of a sequel, “Spinal Tap II: The End Continues,” making it especially timely to reflect on the original film’s immutable power.

The secret to that, I suspect, lies in a surprise element: its melancholy. The three main men of Spinal Tap are largely oblivious to the sadness of their own circumstances. Facing ever-mounting interpersonal tensions, creative dead ends and a steeply declining audience share, they soldier on, lost in the fading dream of their onetime relevance and insulated by the frequently moronic bubble of the traveling band.

This modern archetype might be their ultimate rock ’n’ roll creation: the loser so lovable that no one has the heart to tell them the score.

This is an excerpt from a Washington Post story.

A Fine Line Between Stupid and Clever: The Story of Spinal Tap

By Rob Reiner, Christopher Guest, Michael McKean and Harry Shearer with David Kamp (Gallery, $35)